Revelations From Finally Reading Frankenstein After Watching So Many Adaptations

Mary Shelley’s masterpiece is over 200 years old but still has surprises to reveal, even after countless adaptations

Frankenstein is a novel we’ve all convinced ourselves we’ve pretty much read even if we haven’t. There have been so many adaptations and reinterpretations, the characters and ideas and themes have become so engrained in popular culture and inspired so much in the 200+ years since Mary Shelley’s novel was first published, that I certainly felt intimately familiar with the source material despite never picking it up. I was wrong. Having just read the novel, it still contains surprises. As with my discussion of Dracula earlier in the year, this article is less a review and more a highlighting of the various aspects I found revelatory when reading, despite having seen so many adaptations of the work.

The first surprise, found right at the very start with the dating of the first epistolatory letter entry, is that Frankenstein is a period novel. While the entire point of Dracula was transposing an ancient evil into modernity, Frankenstein, the novel about scientific overreach, is set during some undisclosed time in the previous century. Given the advancements it describes, I was shocked the novel wasn’t set in Shelley’s present, if not the not-too-distant-future. Instead, it’s set before her birth. But I guess that highlights another major surprise: the book is less concerned with science than the adaptations would suggest.

It is man’s hubris that is damned, not the nebulous method in which he presents it. Victor Frankenstein, a student of medicine and science, discovers the secret of life but there is no actual discussion on what that secret is. He may bestow animation on lifeless matter but there is no mention of how, only “I collected the instruments of life around me.” The story could easily be set hundreds of years earlier, with alchemy the key rather than science. The novel is science fiction, a pioneer of the genre, but the science matters startlingly little. Early on, Victor sees a tree struck by lightning explode. I imagine this is where the idea of electricity as a tool comes from for the 1931 adaptation, and so many subsequent versions, but there is no mention of it in the novel’s experiments. Only a vague mention of a “spark of life,” which likely isn’t literal.

But best not get too far ahead. The novel begins in the arctic, with a story that bookends the novel, featuring Walton, an adventurer on a voyage of discovery. He seeks “a country of eternal light,” a literal undiscovered country while Victor trespasses on Shakespeare’s metaphorical one. This section is rarely included in adaptations, and I only know it from Kenneth Branagh’s film version. I agree it’s probably unnecessary in most adaptations but it serves a clear purpose in the novel. The parallels between Walton and Frankenstein, who is found hunting his creature upon the ice, are not very subtle. Victor tells his story to prevent Walton on travelling down the same damned path of hubris. What did surprise me however is that Walton is not an experienced captain but very much like a young Frankenstein, a rich kid who has bought a ship and hired a crew based on a childish dream.

Before focusing on resurrection of the flesh, Victor searches for the philosopher’s stone and the elixir of life, and tries to master incantations to rise ghosts and devils. It’s very much a novel of superstition and perhaps even the supernatural, depending on your reading of it. Frankenstein’s success in creating life can be seen as a supernatural occurrence as much as scientific. At times I found Shelley’s inclusion of such elements to hurt the point she makes about very human folly. While Frankenstein’s personal pride and vanity is said to be his undoing, there is also much talk of fate, of the “Angel of Destruction.” “Destiny was too potent, and her immutable laws had decreed my utter and terrible destruction.” It’s hard for his tale to be a warning to Walton when divine or cosmic forces are ultimately in control.

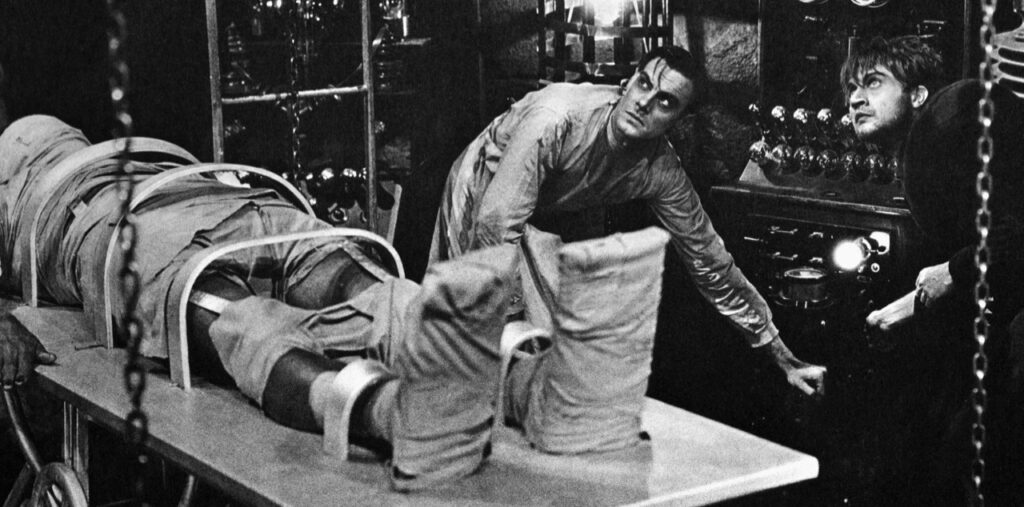

Victor is alone when he makes his monster. This is a key point in the book, which details the impact of loneliness and human connection. He’s not off in some gothic castle by his home, or in a private lab in his house. He’s at school, isolated, in another country, something the films rarely adapt. His friend Henry isn’t there and there’s certainly no Fritz. Just years by himself and great distance from his loved ones, which is very important. Victor has too separate worlds, which then come together most disastrously. He learns what happens in Ingolstadt doesn’t stay in Ingolstadt.

Frankenstein creates life, in a single paragraph. No grand process or explanation forthcoming, his creation lives. And this isn’t a dead man brough back to life. Not old body parts stolen from graves, or hanged criminals. Certainly not the brain of a psychopath, like James Whale’s classic film. Victor acquires bones as a frame but that’s it. The rest is brand new, the individual components of flesh concocted somehow or other. Victor aims to create life rather than stop death, like in the adaptations. When his loved ones later die, he doesn’t conceive of resurrecting them. His creature is something new; a new species rather than a human.

8 feet tall, strong, agile, and made to be beautiful. But Victor gets the proportions wrong. While the monster has lustrous hair and pearly white teeth, his creator sees him as a demon rather than an angel. Victor’s switch from joy to horror is immediate. I would say too fast. I also had this issue with the 1994 film, and it was interesting to see it held true for the book, too. A second after creating him, Victor flees. The story is about the issues and implications of the creation, that is enforced and discussed many times, that it’s the hubris to create that is horrific, to play God, yet it seems like the true horror is with the rejection. If he accepted the creature, would things have turned out badly at all?

We’ll never know. Victor returns to his old life in Switzerland and the creature exits the story for the next two years until Victor’s young brother William is murdered. I enjoyed the trial of the servant Justine for his murder, a scapegoat the authorities hang. It renews Victor’s guilt in a fresh way, that he is responsible for both William’s death and Justine’s because he knows his creation must be the true culprit. I enjoyed less so the reveal that the creature purposefully pinned the murder on Justine, planting evidence upon her person while she slept. That feels too convenient and manipulative when I prefer the consequences of Victor’s actions growing outwards in unexpected ways than being all part of a masterplan.

Finally, Frankenstein and his creation meet and.. talk. The monster is very well spoken, having learnt from books and spying on conversations, rather than being restricted to grunts or broken English. He reveals he was not born as a blank slate but inherently virtuous and benevolent. Frankenstein’s rejection of him turns him to monster. Again, so why is the creation itself deemed the true horror by both Frankenstein the character and ultimately Shelley? If it is a case of Promethean hubris, having the monster begin at a place of good is an odd choice.

But man and monster bond over how miserable they both are. “I was benevolent and good; misery made me a fiend.” Like a lot of gothic fiction (I’ve also recently read Wuthering Heights) Frankenstein is very melodramatic. There’s a lot of characters decreeing how terrible it all is and contemplating suicide when a minor inconvenience happens. But I have to say usually older books can be turgid or stale in their prose. Tough to read. This was not. It flowed quickly and I had to check the version I was reading wasn’t abridged or edited, which is always a danger of novels in the public domain.

The middle six chapters of the book are concerned with the creature’s tale, catching us up on the last two years of his life, from birth to revenge quest, and it’s amazing. This is the highlight of the novel. First he discovers his senses, then his emotions, and then he takes secret refuge in a house that becomes the school in which to study human nature, connection, morality, and his advanced, truncated microcosmic journey through inner and outer humanity leads to, of course, existentialism. I loved these chapters. Shelley does magnificent work in making us connect to the creature, making the pain of his eventual rejection by the family he’s watched and imagined being a part of for two years searingly painful. The page count of this section is well spent, and fleshed out more than any rushed attempt in film. Only the beautifully simple scene with the blind man in Bride of Frankenstein comes close. Yet I will say I didn’t need the soap opera backstory of the cottage family, but maybe the creature’s own interest in that speaks something of human nature.

“Increase in knowledge only discovered to me more clearly what a wretched outcast I was.” The monster is reviled by every human he encounters and this hatred bubbles into revenge against his creator. Frankenstein’s world will be destroyed unless he creates a female counterpart for the monster to share his life with. This is where the more expansive storytelling of the book becomes a weakness for me. The plot has picked up steam and yet suddenly it turns into a travelogue. Victor travels from Switzerland to London, and then the Orkneys to create his second creature. It takes too long to literally get there, with Shelley’s experience as a travel writer coming to the fore and making for a dull few chapters for the modern reader. The only insight is that the alpine landscape brings to mind the artistry and majesty of the almighty’s power and creation, which Frankenstein has bastardised.

Surprisingly for me, the female creature, never referred to as ‘the Bride’, is left a lump of inanimate matter that Victor destroys rather than imbue with life, enraging the creature. Victor again succumbs to misery, imprisoned for the murder of Henry in Ireland (the monster’s doing), unfairly persecuted like his creation, but the difference being his father comes and saves him, bringing him home when he had written off his life, in jail and taking laudanum. Then Elizabeth revives his spirits and marries him. This shows what the monster doesn’t have. He’s alone, and vows to make Victor alone. There’s an intense focus on friendship as a key human trait, a necessary trait. Even Walton just wants a friend. The creature is lacking this connection, and it turns him bitter and violent.

The creature takes his revenge, killing Elizabeth on her wedding night, and Victor’s father dies of shock soon after. Now both creator and creation are alone but for each other, and so begins a chase across the globe for further vengeance. This chase, glossed over quickly in a single chapter, could be a film unto itself, like the ‘Dracula on a boat’ movie born from a lone chapter of that book. At one point, even Frankenstein and the monster are on the same ship but stay hidden from one another. And the monster is armed with “a gun and many pistols” so I’m thinking an action movie.

It’s also here where we see a return of the divine/supernatural to the tale. Frankenstein claims divine intervention keeps the chase going, sending him rain when he’s dying of thirst in the desert or food when hungry. Elizabeth is also described as an angel: “a being heaven-sent, and bearing a celestial stamp”. I knew playing God was a key theme of the book but I wasn’t expecting the religious aspects to be so literal and prominent.

The ending returns us to the beginning, Frankenstein’s story told as Walton becomes the narrator again, detailing how Victor succumbs to illness and exhaustion and his creature vows to die from self-immolation at the North Pole, seeking to repent in a fairly unclimactic way. Shelley’s ending does seem to muddy some of the novel’s thematic work, or perhaps intentionally complicate it in a way I’m unsure of. From all I’d heard I was expecting the novel to be a much clearer morality lesson. Victor warns against ambition but then demands he and Walton continue to push northwards in pursuit of the monster, negating Walton learning the lesson Victor has spent days teaching him. Even Walton says “I had rather die than return shamefully – my purpose unfulfilled.” So has Victor’s tale had any effect, and is the lack of one the ultimate point?

The impetus of Frankenstein is a well known story. Mary Shelley, her husband Percy Shelley, and Lord Byron on a dark and stormy night in Switzerland tasking each other with creating a horror story. Mary held on to hers and developed it into the famous novel, yet the most surprising thing about it, reading today, is that it is only briefly a horror story. The monster is scary in the initial encounter, and formidable at the end, but the novel doesn’t linger on thrills or chills. It is horror and it is sci-fi, but more so it’s a classic story of revenge between two men (or one man and one neo-man), reminding me most of The Count of Monte Cristo. The novel is rich but even more so feels almost tailor-made for expansion of themes and ideas. It holds the kernels of many concepts, making it a work ripe for adaptation and iteration, even after 200 years.