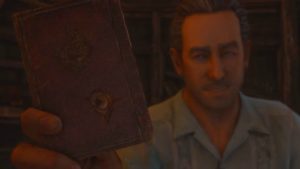

The first time we see Nathan Drake he’s jamming a crowbar into an ancient coffin; it’s hard to think of a more perfect opening image for the Uncharted series. Drake may be a tenacious, unsubtle, rough-around-the-edges everyman with questionable levels of professionalism, but since the release of Uncharted: Drake’s Fortune, developer Naughty Dog have become most unlike their beloved hero, known as perfectionists in regards to both gameplay and deep, rich storytelling. Revisiting the first game in the series, almost fifteen years after its release exclusively on PlayStation 3, and going on the adventure to obtain “El Goddamn Dorado” once again is a nostalgic trip that speaks not only of the game’s enduring legacy but also highlights the innovation and confidence that has grown in the years since.

Brevity is the key word when it comes to the storytelling approach of Uncharted: Drake’s Fortune. Not only is the plot set up in very short cinematics but the characterisation and relationships are speedily illustrated too. Unlike its sequels or other Naughty Dog titles, there are no sizable sections without combat or cutscenes dedicated to character growth. It’s an action game, a fun blockbuster, and tries to be nothing more. There are no pauses and while this is a deliberate choice, I feel it shows a lack of self confidence from the developers. They are so worried about whether they can keep the gamer’s attention without constant stimuli literally shooting at them that they don’t try to tell much of a story, and the game lacks the depth of the sequels. This desire to not stray away from action also actually harms the logic of the game. Nate opens a tomb sealed for hundreds of years and bad guys are already in there, despite the fact they were trying to get in there a moment before and couldn’t.

Brevity is the key word when it comes to the storytelling approach of Uncharted: Drake’s Fortune. Not only is the plot set up in very short cinematics but the characterisation and relationships are speedily illustrated too. Unlike its sequels or other Naughty Dog titles, there are no sizable sections without combat or cutscenes dedicated to character growth. It’s an action game, a fun blockbuster, and tries to be nothing more. There are no pauses and while this is a deliberate choice, I feel it shows a lack of self confidence from the developers. They are so worried about whether they can keep the gamer’s attention without constant stimuli literally shooting at them that they don’t try to tell much of a story, and the game lacks the depth of the sequels. This desire to not stray away from action also actually harms the logic of the game. Nate opens a tomb sealed for hundreds of years and bad guys are already in there, despite the fact they were trying to get in there a moment before and couldn’t.

This shying away from narrative depth would be more of a problem if Naughty Dog didn’t do little conversations and interactions during gameplay better than anyone else. Whether it’s casual banter or plot details, the chatter between characters as you explore and fight your way through the game world is engaging and well written. It’s in these moments where the characters shine and why Nate, Sully, and Elena are so well loved. The acting and writing is pitch perfect – quippy but not annoying, and full of micro doses of character information. The game’s worst sections are easily those that find Nate alone, with no one else to bounce off of, making the gunfights and constant grunting by Nolan North grow tiring. One conversation that has always stuck in my mind is at the very start when Nate teaches Elena how to shoot a gun, and not just because of how accepting of mass murder everyone is in this series. Is there another game where a character gives a tutorial but the player is in control of the teacher rather than the student?

The action of Drake’s Fortune is largely contained to a single tropical island, and the lack of diverse environments makes the game’s already repetitive action feel even more so. For the first time playing Uncharted, I did find myself getting bored at some sections. At the halfway point, the jungle gets notably darker and overgrown, and the pirate baddies are replaced with mercenaries with supposedly better guns, but it feels purely cosmetic. A brief reprieve comes from the level set in the sunken city but even this feels like the jungle, just surrounded by walls. There’s no new gameplay, the inability to dive while swimming hampers traversal, and there’s not enough elevation despite the tall buildings. In general, the game plants the player in a location for too long without moving on; by the end of the game, you’ve had to fight through the same church on three separate occasions.

The action of Drake’s Fortune is largely contained to a single tropical island, and the lack of diverse environments makes the game’s already repetitive action feel even more so. For the first time playing Uncharted, I did find myself getting bored at some sections. At the halfway point, the jungle gets notably darker and overgrown, and the pirate baddies are replaced with mercenaries with supposedly better guns, but it feels purely cosmetic. A brief reprieve comes from the level set in the sunken city but even this feels like the jungle, just surrounded by walls. There’s no new gameplay, the inability to dive while swimming hampers traversal, and there’s not enough elevation despite the tall buildings. In general, the game plants the player in a location for too long without moving on; by the end of the game, you’ve had to fight through the same church on three separate occasions.

Unlike its memorable sequels, there is no single defining action set piece in Drake’s Fortune. No plane, train, or cruise ship. In fact, the jet ski sections are as close as the game comes and they are terrible. The blasted thing acts like a dodgem, bouncing off the sides of buildings and rocks. There’s no real controlling of it, rather just trying to point it in the right direction and pray you don’t hit a mine. Having to drive up some rapids against the current is mighty frustrating. Whenever Elena hops on the back, she suddenly has an infinite grenade launcher but the player can’t shoot and drive at the same time. The entire procedure is awkward: drive a distance up the river, stop, shoot the mines heading at you, and hope the river hasn’t pushed you back too far for the next set of mines to reach you as you drive forwards again.

Perhaps the game’s greatest feature is one I never thought about while playing the game when I was younger, something invisible and yet controls everything you see. I’m talking of the camera. The game rarely likes to switch to alternate angles, instead following Nate from behind during combat and then smoothly gliding alongside while climbing. The moments where it pulls out to create a sense of scale before pushing inwards again are wonderful. While improved enormously going forward, the sense of movement for a 2007 game is very good. Just the way Nate runs, with his little flapping arms, feels natural and there’s a smooth ease to the aiming and traversal. Well, most of the time. Nate’s little hop is silly and there are those Assassin’s Creed-esque moments where you jump awkwardly in the wrong direction, miss a grabbable point, or just fail to interact with a ladder and fall to your death. I was also very pleased to see that the Nathan Drake Collection version of the game has done away with the terrible motion sensor sections when balancing on logs. Good riddance.

Perhaps the game’s greatest feature is one I never thought about while playing the game when I was younger, something invisible and yet controls everything you see. I’m talking of the camera. The game rarely likes to switch to alternate angles, instead following Nate from behind during combat and then smoothly gliding alongside while climbing. The moments where it pulls out to create a sense of scale before pushing inwards again are wonderful. While improved enormously going forward, the sense of movement for a 2007 game is very good. Just the way Nate runs, with his little flapping arms, feels natural and there’s a smooth ease to the aiming and traversal. Well, most of the time. Nate’s little hop is silly and there are those Assassin’s Creed-esque moments where you jump awkwardly in the wrong direction, miss a grabbable point, or just fail to interact with a ladder and fall to your death. I was also very pleased to see that the Nathan Drake Collection version of the game has done away with the terrible motion sensor sections when balancing on logs. Good riddance.

Thus far, despite counting myself a devout fan of the franchise’s story and characters, I’ve yet to really mention the game’s narrative. It’s… acceptable. It’s a story that simply pushes you through each combat encounter and location with few flourishes. It’s an introduction to the series, a prologue, rather than a full, meaty chapter. The villains likewise are fairly bland. There are hints at a past between Nate and Eddy Raja but this is left unexplored. Gabriel Roman is like a boring version of Belloq from Raiders of the Lost Ark – even that film needed the added villainous spice of some Nazis. Roman is killed at the end by his protégé Navarro, a supposed twist but simply exchanging one rubbish villain for another is far from satisfying. There is potential with Navarro however. He was found in a slum and essentially raised by Roman, very similar to Sully’s relationship with Nate. If the game were made later, the writers would likely explore this parallel, but as it stands it’s interesting in retrospect knowing the events of Uncharted 3 but likely unintentional.

It’s impossible not to bring the knowledge and insight learnt from the game’s sequels back to the original when revisiting it, and in this respect the game is a bit of a mixed bag. One of the very first lines uttered by Nate is “you obviously haven’t been in a Panamanian jail”, which lines up perfectly with Uncharted 4 where we see Nate in a Panamanian jail in a flashback set before Drake’s Fortune. On the other end of the spectrum however is Nate’s reaction to Sully’s supposed death. The old man is gunned down by Gabriel Roman early on, secretly surviving thanks to the old bullet-stopping-diary-in-chest-pocket trick. Nate however doesn’t seem to care. There’s no grieving, he just runs away and never mentions it. The two have a rapport but by the game’s logic they could have been working together for only a month or so, and it doesn’t fit with the backstory given in Uncharted 3 of them having a deep relationship for years.

It’s impossible not to bring the knowledge and insight learnt from the game’s sequels back to the original when revisiting it, and in this respect the game is a bit of a mixed bag. One of the very first lines uttered by Nate is “you obviously haven’t been in a Panamanian jail”, which lines up perfectly with Uncharted 4 where we see Nate in a Panamanian jail in a flashback set before Drake’s Fortune. On the other end of the spectrum however is Nate’s reaction to Sully’s supposed death. The old man is gunned down by Gabriel Roman early on, secretly surviving thanks to the old bullet-stopping-diary-in-chest-pocket trick. Nate however doesn’t seem to care. There’s no grieving, he just runs away and never mentions it. The two have a rapport but by the game’s logic they could have been working together for only a month or so, and it doesn’t fit with the backstory given in Uncharted 3 of them having a deep relationship for years.

Uncharted has a weird relationship with the supernatural. On one hand it wants to stay somewhat gritty and grounded, and on the other it recognises that shooting monsters is quite fun. Drake’s Fortune features the zombie-like Descendants but the game refuses to just say that the treasure is cursed, as if the developers are embarrassed by it without attempting some scientific explanation to validate their choice. Like 28 Days Later, there’s a virus that turns people into monsters, housed within the golden sarcophagus. I’ve never needed this added detail and wish they just committed to the supernatural aspect. However, the sequences featuring these Descendants are genuinely scary, a far greater push towards horror than I remember or the sequels will attempt. It’s also fun seeing the mercenaries and Descendants fight each other during the finale, although we’re a long way off from pitting Clickers and humans against each other in The Last of Us Part 2.

Drake’s Fortune ends in fairly disappointing fashion. After some great combat encounters in the last hour, the finale finds Nate on a ship for a brief hand-to-hand boss fight with Navarro. Neither boss fights or hand-to-hand combat are the franchise’s strengths, and Navarro and Nate have had zero screentime together to work up a genuine feud. It all feels rather perfunctory. But the true ending is simply Nate and Elena sharing a moment together and out of everything in the game, this is what truly works. The relationships, the characters, the heart of the game that shines through any storytelling or gameplay flaws. It may be more hidden and shine less brightly in the first game than the sequels but the beginning essence is definitely there. I have no doubt that Drake’s Fortune is the weakest of the Uncharted series but the potential is clear to see. To use the franchise’s own words, the first game is a small beginning. Sic Parvis Magna: greatness from small beginnings.

Drake’s Fortune ends in fairly disappointing fashion. After some great combat encounters in the last hour, the finale finds Nate on a ship for a brief hand-to-hand boss fight with Navarro. Neither boss fights or hand-to-hand combat are the franchise’s strengths, and Navarro and Nate have had zero screentime together to work up a genuine feud. It all feels rather perfunctory. But the true ending is simply Nate and Elena sharing a moment together and out of everything in the game, this is what truly works. The relationships, the characters, the heart of the game that shines through any storytelling or gameplay flaws. It may be more hidden and shine less brightly in the first game than the sequels but the beginning essence is definitely there. I have no doubt that Drake’s Fortune is the weakest of the Uncharted series but the potential is clear to see. To use the franchise’s own words, the first game is a small beginning. Sic Parvis Magna: greatness from small beginnings.

What are your thoughts on Uncharted: Drake’s Fortune? Let me know in the comments and be sure to geek out with me about TV, movies and video-games on Twitter @kylebrrtt.