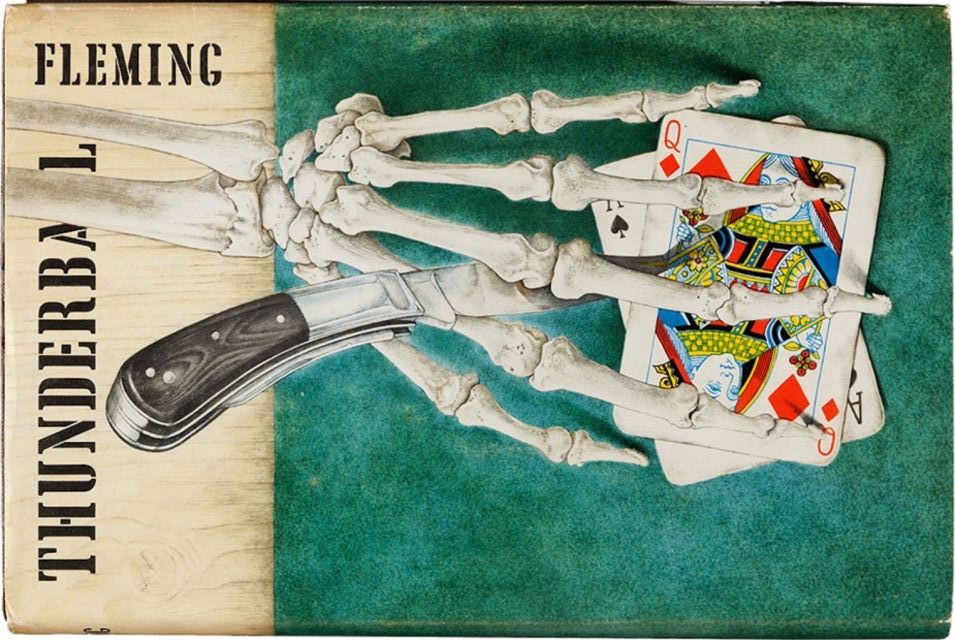

Nine books into the series, Ian Fleming gains a sense of humour. The James Bond novels up to this point have had smarmy witticisms and ludicrous names that may elicit an occasional smile, or more likely a facepalm, but in Thunderball Fleming tries his hand at genuine situational comedy and shockingly it works. It all stems from Bond’s medical which reveals aliments including high blood pressure, liver issues, and fibrosis. The agent may think overindulging in cigarettes and alcohol is a remedy for the stresses of his profession but M disagrees and sends Bond to Shrublands, a health clinic, to detox from food, alcohol, and women.

This all plays like an episode of a classic British sitcom – the irritable lead character sent off somewhere far out of his comfort zone to react to and mock the treatments. Thunderball has a complex conception, the novel sprouting from an unproduced screenplay Fleming co-wrote, and the opening feels very much like a bizarre addition barely connected to the rest of the story to stretch the narrative into one long enough for a novel. It may not gel with what is to come but as a short Bond adventure it’s an entertaining read. Where we would once get M briefing Bond on a mission, we now see him lecturing him on his “unnatural way of life”. It’s purely a comedy, especially with Bond now furious and overreacting to everything simply because he’s been told he should eat more yogurt: “M was a dangerous lunatic – a danger to the country. It was up to Bond to save England.” He’s a radically different character to the one we met in Casino Royale but, as with The Hildebrand Rarity, petty Bond is my favourite Bond.

This all plays like an episode of a classic British sitcom – the irritable lead character sent off somewhere far out of his comfort zone to react to and mock the treatments. Thunderball has a complex conception, the novel sprouting from an unproduced screenplay Fleming co-wrote, and the opening feels very much like a bizarre addition barely connected to the rest of the story to stretch the narrative into one long enough for a novel. It may not gel with what is to come but as a short Bond adventure it’s an entertaining read. Where we would once get M briefing Bond on a mission, we now see him lecturing him on his “unnatural way of life”. It’s purely a comedy, especially with Bond now furious and overreacting to everything simply because he’s been told he should eat more yogurt: “M was a dangerous lunatic – a danger to the country. It was up to Bond to save England.” He’s a radically different character to the one we met in Casino Royale but, as with The Hildebrand Rarity, petty Bond is my favourite Bond.

At Shrublands, between all the complaining, Bond encounters and begins a feud with Count Lippe, a member of SPECTRE. This is the very first appearance of the villainous organisation and Bond stumbles upon them by sheer coincidence. Surely there has to be a satisfying middle ground between the coincidence of the books and the overly-personal family angle of the new films – both being equally disappointing. Fleming himself can’t defend the chance encounter, stating that “the whole thing, against the background of Shrublands, was so unlikely and so utterly ridiculous.” The conflict between Bond and Lippe leads to our hero tied to a spine-stretching machine known as ‘The Rack’ while the villain sneaks in to turn the machine up to maximum in a chapter that would be harrowing if it wasn’t Fleming reaching the peak of his sadomasochistic tendencies, and that’s saying something.

“Was he losing the vices that were so much part of his ruthless, cruel, fundamentally tough character? Who was he in the process of becoming?” While much of Bond’s stay at Shrublands is played for comedy, there is some attempt at exploring Bond and his relationship with his vices. After his visit he becomes a different character entirely, now having more energy, patience, and even smiling. It’s like the inevitable trope sitcom episode where the grumpy character is suddenly happy and everyone wonders whether he’s been replaced by a Stepford Wives robot clone or something. It’s the women in Bond’s life – May, Ponsonby, and Moneypenny, who he has his first proper flirtation with in Thunderball – who want the old James back.

“Was he losing the vices that were so much part of his ruthless, cruel, fundamentally tough character? Who was he in the process of becoming?” While much of Bond’s stay at Shrublands is played for comedy, there is some attempt at exploring Bond and his relationship with his vices. After his visit he becomes a different character entirely, now having more energy, patience, and even smiling. It’s like the inevitable trope sitcom episode where the grumpy character is suddenly happy and everyone wonders whether he’s been replaced by a Stepford Wives robot clone or something. It’s the women in Bond’s life – May, Ponsonby, and Moneypenny, who he has his first proper flirtation with in Thunderball – who want the old James back.

The novel makes the case that Bond just isn’t Bond without his vices, that a 00 agent cannot be the toughened individual needed for the job without such things. This is a fascinating idea, and certainly something that could be explored while Bond is on a mission so we can compare and contrast the changes in his character, and yet this thread is wrapped up before he leaves on his primary assignment. Following an assassination attempt by Lippe, who dies in the process, Bond immediately reverts back to his old self and decides his previous lifestyle is necessary. For so much set-up it’s a fast and unsatisfying payoff. While there are mentions of sobriety throughout the book relating to certain characters as a comparison to Bond, all of the novel’s character examination of Bond is contained to the first third, further highlighting Thunderball’s bizarre structure and leaving the rest of the book somewhat shallow.

Thunderball is known as the first entry in Fleming’s SPECTRE trilogy of novels. I had long awaited the organisation’s arrival in the series and it wasn’t a disappointment. I love being privy to SPECTRE meetings in the movies and the book had the same feel as those early films. We get two chapters dedicated to the organisation’s meeting and I enjoy how Fleming doesn’t write anything expositionally. You have to gleam what you can from their conversation and formulate their plan in your head instead of having it spelt out to you, like the reader is secretly listening in on something they shouldn’t be hearing. Very much a private enterprise for private profit, though composed of former members of different governments and syndicates, SPECTRE is an intriguing move away from the real geopolitics of the SMERSH-led early novels. And as a counter to MI6 and Bond, drinking is taboo and smoking frowned upon in SPECTRE.

Thunderball is known as the first entry in Fleming’s SPECTRE trilogy of novels. I had long awaited the organisation’s arrival in the series and it wasn’t a disappointment. I love being privy to SPECTRE meetings in the movies and the book had the same feel as those early films. We get two chapters dedicated to the organisation’s meeting and I enjoy how Fleming doesn’t write anything expositionally. You have to gleam what you can from their conversation and formulate their plan in your head instead of having it spelt out to you, like the reader is secretly listening in on something they shouldn’t be hearing. Very much a private enterprise for private profit, though composed of former members of different governments and syndicates, SPECTRE is an intriguing move away from the real geopolitics of the SMERSH-led early novels. And as a counter to MI6 and Bond, drinking is taboo and smoking frowned upon in SPECTRE.

Introducing Ernst Stavro Blofeld, supposedly Bond’s greatest antagonist, nine books into a series already filled with memorable villains is no mean feat but Fleming does so brilliantly. On the surface he may have the traits of other baddies but in actuality he stands alone. All the other Bond foes are fuelled by insecurity in some way, making up for a flaw or defect, whether real or perceived, but Blofeld isn’t. He’s supremely confident and modeled more on Genghis Khan or Alexander the Great, exuding a powerful animal magnetism with a quality of relaxation. Blofeld also has a sense of honour and after a kidnapped woman is raped by one of his men, he returns her with the ransom money and kills the SPECTRE agent responsible. His sin, if any, is pride. He doesn’t smoke or drink or have sex and barely eats. He is very much the anti-Bond, and his small tease of an appearance here makes me very excited to read the following novels when the two come face-to-face.

SPECTRE have stolen two nuclear weapons and plan to use them unless Britain and the United States pay a ransom, and while this may now be a standard set-up for an action thriller plot, it feels different for Fleming’s Bond series. So far, the stories have been relatively small scale, or at least begin that way, with inciting incidents being a single assassination or an individual cheating at cards. Neither have we seen MI6 in the midst of an emergency before. Once the extortion letter is received, there’s no casual conversations in comfy leather chairs, instead everyone is at action stations. The secret service is actually on the backfoot for once and this is refreshing to read, adding some extra zest to the formula. Every intelligence service on the planet begins to work this single case, dubbed Operation Thunderball, and Bond, usually a lone operator, is but one small cog in the machine, albeit on his own mission in the Bahamas where M has a hunch the bombs are located.

SPECTRE have stolen two nuclear weapons and plan to use them unless Britain and the United States pay a ransom, and while this may now be a standard set-up for an action thriller plot, it feels different for Fleming’s Bond series. So far, the stories have been relatively small scale, or at least begin that way, with inciting incidents being a single assassination or an individual cheating at cards. Neither have we seen MI6 in the midst of an emergency before. Once the extortion letter is received, there’s no casual conversations in comfy leather chairs, instead everyone is at action stations. The secret service is actually on the backfoot for once and this is refreshing to read, adding some extra zest to the formula. Every intelligence service on the planet begins to work this single case, dubbed Operation Thunderball, and Bond, usually a lone operator, is but one small cog in the machine, albeit on his own mission in the Bahamas where M has a hunch the bombs are located.

Thunderball bounces around in time and structure because as soon as Bond is sent on his mission, we flash back to see how SPECTRE acquired the weapons using a rogue pilot named Petacchi. As soon as he touches down however, he’s murdered by Largo, SPECTRE’s second-in-command and the novel’s primary antagonist, which is something of a disappointment. Largo is serviceable as a villain but after the great reveal of Blofeld he’s boring in comparison. Aboard his yacht, the Disco Volante, Largo’s described as the type of man who some two hundred years before would have been a pirate. Imagining him as Blackbeard throughout the story was the way I tried to make him more interesting in my mind. One might presume his piratical nature would inform his personality but instead Largo’s most discussed trait is his sense of calm, which doesn’t seem to fit. He also has a notable physical attribute too of course, maybe the least interesting one yet, being endowed with huge hands “almost like large brown furry animals quite separate from their owner.”

Largo’s flaw is his vices, being unable to function without a woman in his reach, which will prove to be his downfall – another underexplored connection to Bond’s similar sensibilities. The woman in question is Dominetta Vitali, who Bond tracks and uses to get close to Largo. Domino is perhaps the Bond girl I had the biggest change of opinion about as I was reading. She’s introduced as this independent girl of authority who drives like a man, which is an observation Fleming always makes about his female characters, and it initially feels like Fleming’s attempt at a strong character out for herself who is revealed to be nothing of the sort when she’s enslaved by her instant infatuation of Bond. While this still happens to some degree, each pole of this characterisation is more dynamic than with previous love interests, when it’s revealed she’s already enslaved.

Largo’s flaw is his vices, being unable to function without a woman in his reach, which will prove to be his downfall – another underexplored connection to Bond’s similar sensibilities. The woman in question is Dominetta Vitali, who Bond tracks and uses to get close to Largo. Domino is perhaps the Bond girl I had the biggest change of opinion about as I was reading. She’s introduced as this independent girl of authority who drives like a man, which is an observation Fleming always makes about his female characters, and it initially feels like Fleming’s attempt at a strong character out for herself who is revealed to be nothing of the sort when she’s enslaved by her instant infatuation of Bond. While this still happens to some degree, each pole of this characterisation is more dynamic than with previous love interests, when it’s revealed she’s already enslaved.

As we get to know her, Domino is revealed to be a bird in a gilded cage, a kept women under Largo’s control who pretends otherwise. Her desire towards Bond is more as a means of escape. She has a fairytale fantasy about her cardboard hero, the man on the Players cigarette carton, who she fantasises will come and save her. I loved hearing her tell this story and it suddenly made her sad and sympathetic. Domino believes Bond can be that hero, again being another tie between James and the heroic nature of cigarettes and vices. These character beats could make Domino feel weak and nothing but a poor damsel in distress but it does the opposite. Fleming takes this stereotypical character framework and fills it with a real strength of character. I like her relationship with Bond because it’s not pretending to be something it is not: namely, love. Feelings and attraction are at play and make their relationship dangerous but both use each other in the end: Bond to get Largo and Domino to escape. Bond even regrets sleeping with her, which feels totally new, and the two feel more like compatriots than lovers.

If Thunderball is a love story then it’s not between Bond and Domino but rather Bond and Felix Leiter. Bond is just so happy to see his mate at the airport: “Bond swung round. It was! It was Felix Leiter!” The two friends are reunited when Felix is reinstated into the CIA and becomes Bond’s partner for the entire second half of the novel. I do like Felix but I’m growing a little tired of the character by this point. Often it does feel like Fleming has included the American just to give Bond someone to talk to, with there being pages of long dialogue between them instead of what could have been inner monologues, perhaps an unwelcome leftover from the story’s origin as a screenplay. Yet whenever Bond and Leiter act as mouthpieces for their countries I’m thankful for his inclusion. With SPECTRE, the books are becoming more apolitical, but there are still some insights from the era, with Felix stating America feels more secure than Britain, where Bond claims it doesn’t feel like the war ever ended.

If Thunderball is a love story then it’s not between Bond and Domino but rather Bond and Felix Leiter. Bond is just so happy to see his mate at the airport: “Bond swung round. It was! It was Felix Leiter!” The two friends are reunited when Felix is reinstated into the CIA and becomes Bond’s partner for the entire second half of the novel. I do like Felix but I’m growing a little tired of the character by this point. Often it does feel like Fleming has included the American just to give Bond someone to talk to, with there being pages of long dialogue between them instead of what could have been inner monologues, perhaps an unwelcome leftover from the story’s origin as a screenplay. Yet whenever Bond and Leiter act as mouthpieces for their countries I’m thankful for his inclusion. With SPECTRE, the books are becoming more apolitical, but there are still some insights from the era, with Felix stating America feels more secure than Britain, where Bond claims it doesn’t feel like the war ever ended.

Much of the novel’s Bahamas-set second half charts Bond’s investigation into Largo and the location of the bombs and it is boring. We, the reader, know much more than Bond because we’ve switched to the perspective of Blofeld, Largo, and even Petacchi, so for a solid 150 pages Bond is playing catch up, unearthing details already known to us. Other than the occasional flash of character insight from Domino or Felix, a large portion of the book is just straightforward investigating and a far cry from the humorous opening and the cool villain reveal. We learn nothing new about Bond and there are no twists or escalation in the plot. Even the ticking clock of the bombs is underplayed. All the Bond tropes are included, like the meeting with the baddie, the flirtation with the girl, and the trip to the casino, but none feel very exciting.

Yet within this dull block of the narrative, Fleming writes one of the most effective scenes he’s ever written which suddenly awoke me from my half-asleep reading stupor in a fit of excitement and terror. Finally, Bond and Felix discover the submerged plane and dive down to find the bombs missing. Bond getting up close and personal with underwater life is nothing new for Fleming, with memorable sequences in Live and Let Die and Doctor No, but this is the most impressively written encounter yet. It’s a horror scene with Bond finding himself in a red-eyed catacomb, surrounded by octopi and half-eaten corpses. Just below the surface of this Caribbean paradise, these horrors fester and Bond is terrified. I don’t blame him; the description is very unsettling. Our hero refuses to continue on and flees in terror, “hysterically” as Fleming puts it. That is most certainly not a word I was expecting to read in relation to Fleming’s Bond, but it’s a welcome reminder of how human a character he can be.

Yet within this dull block of the narrative, Fleming writes one of the most effective scenes he’s ever written which suddenly awoke me from my half-asleep reading stupor in a fit of excitement and terror. Finally, Bond and Felix discover the submerged plane and dive down to find the bombs missing. Bond getting up close and personal with underwater life is nothing new for Fleming, with memorable sequences in Live and Let Die and Doctor No, but this is the most impressively written encounter yet. It’s a horror scene with Bond finding himself in a red-eyed catacomb, surrounded by octopi and half-eaten corpses. Just below the surface of this Caribbean paradise, these horrors fester and Bond is terrified. I don’t blame him; the description is very unsettling. Our hero refuses to continue on and flees in terror, “hysterically” as Fleming puts it. That is most certainly not a word I was expecting to read in relation to Fleming’s Bond, but it’s a welcome reminder of how human a character he can be.

Domino is revealed to be the sister of Petacchi, but this isn’t part of Largo or SPECTRE’s plan, it’s simply another unbelievable coincidence, and Bond uses the information that Largo killed her brother to turn Domino against him. After being given a mission by Bond, Domino is quickly rumbled offscreen by Largo and tortured. Thunderball thus far has been unafraid to switch perspective characters for chapters but Fleming refuses to dedicate one to Domino when perhaps he should. Once she becomes a key player she is only talked about and doesn’t appear until the ending. Thankfully she escapes captivity and saves Bond’s life, spearing Largo with a harpoon gun. It’s a good moment but very similar to the end of From a View to a Kill. I guess Fleming’s short stories weren’t as widespread as his novels and he could easily get away with repeating scenes from them.

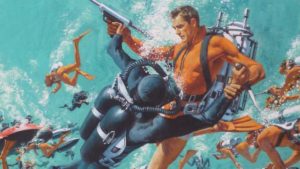

Thunderball concludes with Bond and ten US navy men intercepting Largo and his forces while they are moving a bomb into position, leading to an underwater fight on a previously unseen scale in Fleming’s novels. It’s good action, particularly after such a dull hundred pages, and it’s interesting to see Bond, the lone operator, as a leader of men, giving a classic pre-battle speech aboard a submarine. This truly is Commander Bond. The underwater action works so much better on the page than it does in the film. The slow movement is terrifying rather than boring, with Bond able to see what is happening but not being able to move fast enough to respond. It’s a fight in slow motion but with everyone’s brains working at high speed. The fight is clumsy and brutal, “it was impossible to fight scientifically” as Fleming puts it. Knives slowly puncture skin and black clouds ooze out in a series of visceral deaths, although Largo picking up an octopus to use as a weapon is just too ridiculous. And the nuclear weapon is described as an “obscene rubber sausage”, which is far from threatening.

Thunderball concludes with Bond and ten US navy men intercepting Largo and his forces while they are moving a bomb into position, leading to an underwater fight on a previously unseen scale in Fleming’s novels. It’s good action, particularly after such a dull hundred pages, and it’s interesting to see Bond, the lone operator, as a leader of men, giving a classic pre-battle speech aboard a submarine. This truly is Commander Bond. The underwater action works so much better on the page than it does in the film. The slow movement is terrifying rather than boring, with Bond able to see what is happening but not being able to move fast enough to respond. It’s a fight in slow motion but with everyone’s brains working at high speed. The fight is clumsy and brutal, “it was impossible to fight scientifically” as Fleming puts it. Knives slowly puncture skin and black clouds ooze out in a series of visceral deaths, although Largo picking up an octopus to use as a weapon is just too ridiculous. And the nuclear weapon is described as an “obscene rubber sausage”, which is far from threatening.

The novel’s final chapter is really rather sweet and confirms my feelings on Bond and Domino’s relationship. In hospital, Bond demands to see her and barges into her room. There’s no sexual desire involved, that’s over and not part of their relationship, he just wanted to make sure she was okay and Bond collapses next to her in hospital as they both, finally, rest.

Thunderball suffers from a lack of cohesion. The first third is entertaining and surprisingly funny, but tonally doesn’t fit with the rest of the novel and feels like an expanded version of the mud bath sequence from Diamonds Are Forever. It’s a short story glued onto the front of an existing screenplay that was converted into a novel, and the characterisation it teases is left unexplored. Bond’s nature is questioned until it is needed for a mission and then the rest of the story plays out rather ploddingly and formulaically. I appreciate the changes to the structure, with chapters leaving Bond behind to focus on the perspective of the villains in a way that splits the chronology, but Fleming refuses to change how he tells Bond’s story of investigation in response, leading to the reader simply having to absorb the same information twice. Thunderball is far from Fleming’s best Bond novel but it does have its moments. Domino is a wonderful surprise and ranks among the best ‘Bond girls,’ and the introduction of SPECTRE is a fascinating thread I can’t wait to pull as the series continues.

Thunderball suffers from a lack of cohesion. The first third is entertaining and surprisingly funny, but tonally doesn’t fit with the rest of the novel and feels like an expanded version of the mud bath sequence from Diamonds Are Forever. It’s a short story glued onto the front of an existing screenplay that was converted into a novel, and the characterisation it teases is left unexplored. Bond’s nature is questioned until it is needed for a mission and then the rest of the story plays out rather ploddingly and formulaically. I appreciate the changes to the structure, with chapters leaving Bond behind to focus on the perspective of the villains in a way that splits the chronology, but Fleming refuses to change how he tells Bond’s story of investigation in response, leading to the reader simply having to absorb the same information twice. Thunderball is far from Fleming’s best Bond novel but it does have its moments. Domino is a wonderful surprise and ranks among the best ‘Bond girls,’ and the introduction of SPECTRE is a fascinating thread I can’t wait to pull as the series continues.

Stay tuned to OutofLives for my thoughts on the tenth of Fleming’s Bond novels, The Spy Who Loved Me, in the coming weeks.