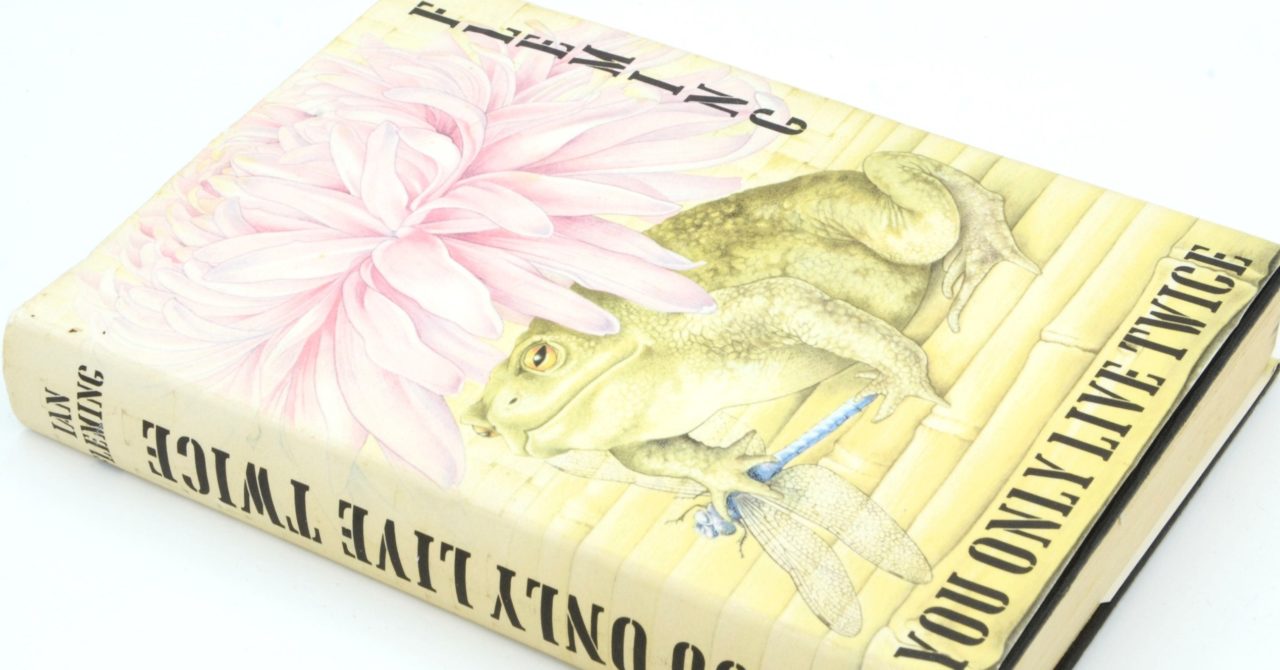

As with most of Ian Fleming’s James Bond stories, You Only Live Twice begins in medias res, but for the first time I feel it shouldn’t have. The first chapter sees Bond in Japan, entertaining a geisha in an okiya, but I didn’t want to jump straight into the next mission. On Her Majesty’s Secret Service was a Bond novel like no other, ending on a note of incredible tragedy with the death of Bond’s wife mere hours after their wedding. I was desperate to read about the aftermath of the previous book, about how Bond has changed, but apparently that has to wait. Instead, Fleming describes a game of Rock Paper Scissors between Bond and his new ally Tiger Tanaka in excruciating detail. He explains the rules of the childhood game that everyone knows more than he ever did chemin de far.

Blessedly, the novel takes a backwards step and returns us to before the mission, although not from James Bond’s perspective. M and a psychologist discuss Bond. Apparently he’s falling to pieces and is close to becoming a security risk, drinking and gambling to excess, which for Bond must be an extraordinary amount. Bond isn’t interested in his job anymore, or even his life. M wants to fire him, there’s no space for a “lame brain” in the service. He’s bungled his last two operations and nearly got himself killed. This is all fascinating characterisation for Bond who is a different man than we’ve ever seen before. But the issue is, we don’t see it now either. Bond is talked about ad nauseam but we don’t experience him at these low points. It would have been great to open the novel with Bond failing one of these missions rather than simply hear about it over lunch with M. Fleming has forgotten the rule of ‘show, don’t tell’.

Blessedly, the novel takes a backwards step and returns us to before the mission, although not from James Bond’s perspective. M and a psychologist discuss Bond. Apparently he’s falling to pieces and is close to becoming a security risk, drinking and gambling to excess, which for Bond must be an extraordinary amount. Bond isn’t interested in his job anymore, or even his life. M wants to fire him, there’s no space for a “lame brain” in the service. He’s bungled his last two operations and nearly got himself killed. This is all fascinating characterisation for Bond who is a different man than we’ve ever seen before. But the issue is, we don’t see it now either. Bond is talked about ad nauseam but we don’t experience him at these low points. It would have been great to open the novel with Bond failing one of these missions rather than simply hear about it over lunch with M. Fleming has forgotten the rule of ‘show, don’t tell’.

In modern parlance, Bond is suffering from PTSD but this is the sixties and his doctor recommends some hypnosis and tells him to get laid. Men don’t talk about emotions and Fleming isn’t going to start now: nobody even mentions Tracy to Bond at MI6, they just try and ignore it. Bill Tanner finally reappears after many a book and despite being described as “Bond’s best friend at the service” I don’t feel like they have a relationship. I wish Tanner appeared more and actually served the purpose Fleming thinks he does. Bond, amidst his heavy drinking, isn’t all that insightful either. Of Bond’s mindset, Fleming writes “Suddenly he felt really bad about everything.” The quality of writing in You Only Live Twice is overall much poorer than the highs of the previous novel. In an attempt to revive Bond’s spirit, M gives him a promotion, the new number of 7777, and an impossible mission. He’s to become a diplomat and create new ties with Japanese intelligence.

Bond wants to shed his old skin on the mission and “he didn’t even mind if the colour of the new skin was to be yellow.” Venturing east for the first time means that two classic staples of Fleming’s writing make a return: casual racism and the travelogue. In Tokyo, Bond meets his contact Tiger Tanaka and the two have a great rapport. The local guide is a trope in Bond stories but Tiger is different. Instead of being the usual international equal at Bond’s beck and call, Tiger is the equivalent of M and can pull rank, which makes for a fun dynamic. A genuine connection grows between Bond, Tiger, and fellow agent Dikko Henderson. “Outside working hours the three men became wellnigh inseparable.” Fleming may not put the work in when it comes to showing Bond at his lowest but having him slowly return to his old self through his new male friendships is executed surprisingly well. It makes for an interesting first 100 pages or so, even if a lot of it consists of Bond being lectured to, first by Dikko and then Tiger.

Bond wants to shed his old skin on the mission and “he didn’t even mind if the colour of the new skin was to be yellow.” Venturing east for the first time means that two classic staples of Fleming’s writing make a return: casual racism and the travelogue. In Tokyo, Bond meets his contact Tiger Tanaka and the two have a great rapport. The local guide is a trope in Bond stories but Tiger is different. Instead of being the usual international equal at Bond’s beck and call, Tiger is the equivalent of M and can pull rank, which makes for a fun dynamic. A genuine connection grows between Bond, Tiger, and fellow agent Dikko Henderson. “Outside working hours the three men became wellnigh inseparable.” Fleming may not put the work in when it comes to showing Bond at his lowest but having him slowly return to his old self through his new male friendships is executed surprisingly well. It makes for an interesting first 100 pages or so, even if a lot of it consists of Bond being lectured to, first by Dikko and then Tiger.

With the dissolution of SPECTRE, You Only Live Twice marks the return of geopolitics to the novels, with Fleming commenting on actual organisations, peoples, and governments. There are fascinating insights into the time it was written, such as the fragile relationship between various intelligence organisations. Britain is left out of a US-Japan alliance, with Bond having to pose as an Australian initially to win round Tiger. England is losing its importance to the world, much like Bond himself. There is no action whatsoever for the first half of the novel but I didn’t mind for most of it. There seemed to be an actual point to Fleming’s discussions of politics this time, and many chapters read like his own version of The Chrysanthemum and The Sword. A guide to understanding how the Japanese, “a separate human species”, do business, including their honour system. It’s often fascinating before it drifts into outdated stereotypes and endless monologues. Yet even at its best, the book is still crying out for an actual plot.

Thankfully the plot finally arrives, although disappointingly in the form of another monologue by Tiger. He tells the tale of Guntrum and Emmy Shatterhand who have recently arrived in Japan and taken up residence in an old castle. The mysterious couple (it’s pretty obvious who they actually are) have created a poison garden and menagerie, a place so dangerous that Blofeld Guntrum has to walk the grounds in a suit of 17th century armour just to stay safe. “What a daft set-up” says Bond, Fleming once again blisteringly self-aware of how preposterous his books have gotten. It may be daft but it is also undeniably fun. Yet we learn all this through exposition, first a speech by Tiger and then a textbook listing poisons, which makes for an incredibly dry five pages of reading. Hundreds are flocking to the castle to commit suicide making it become a national embarrassment for Japan. Tiger tasks Bond with entering the castle and slaying the dragon – Shatterhand – within.

Thankfully the plot finally arrives, although disappointingly in the form of another monologue by Tiger. He tells the tale of Guntrum and Emmy Shatterhand who have recently arrived in Japan and taken up residence in an old castle. The mysterious couple (it’s pretty obvious who they actually are) have created a poison garden and menagerie, a place so dangerous that Blofeld Guntrum has to walk the grounds in a suit of 17th century armour just to stay safe. “What a daft set-up” says Bond, Fleming once again blisteringly self-aware of how preposterous his books have gotten. It may be daft but it is also undeniably fun. Yet we learn all this through exposition, first a speech by Tiger and then a textbook listing poisons, which makes for an incredibly dry five pages of reading. Hundreds are flocking to the castle to commit suicide making it become a national embarrassment for Japan. Tiger tasks Bond with entering the castle and slaying the dragon – Shatterhand – within.

The first stage of the plan is to disguise Bond as a Japanese man. The adaptation of this part of the story in the film is one of the cringiest moments in the Bond canon – seeing 6ft 2 Sean Connery transform into a small Asian man by putting on a wig, darkening his skin, and taping his eyes. It’s still silly in the book but much easier to pull off when we don’t actually have to see the results, only read about them. The changes are more subtle, and Bond has to pretend to be deaf and dumb to explain his lack of language skills. But when it comes to his cover, it’s less the Japanese way of life that puzzles Bond but their way of death. Death is a key theme of the novel, unsurprisingly with Tracy’s death hanging over everything. Every chance Fleming gets he’ll use terms relating to death, however seemingly innocently, such as “sleep like the dead.” References are everywhere and Bond can’t escape them. It feels like he’s marching towards his end, something I would be convinced of if I didn’t know more books were coming. Bond, who doesn’t care about living anymore, has to travel to the suicide capital of the world, a place of death. Will he overcome or succumb?

While on their way to Chez Shatterhand, Bond and Tiger journey across Japan together like they are hosting a travel show. Fleming has certainly flirted with the James Bond travelogue before but this takes it to another level, being nothing but Sake and sightseeing for 50 pages. They feed beer to a cow, eat a live lobster, visit the oldest whorehouse in Japan, witness Ninjas in training, and even go on a haiku course. Next up, paddleboarding with Romesh Ranganathan and minigolf with Joe Lycett. Unlike the other activities, the haiku-writing does offer some insight into Bond’s character, however. While he can’t get to grips with the format (seven syllables in the middle, five in the first and last line. If you ain’t poetic no need to sweat it, haikus don’t need to rhyme) it’s a great piece of poetry that gives the book its title: “You only live twice; once when you are born, and once when you look death in the face.” It reveals Bond’s mindset more than the lame opening chapters and builds further foreboding for his journey into Shatterhand’s Hell.

While on their way to Chez Shatterhand, Bond and Tiger journey across Japan together like they are hosting a travel show. Fleming has certainly flirted with the James Bond travelogue before but this takes it to another level, being nothing but Sake and sightseeing for 50 pages. They feed beer to a cow, eat a live lobster, visit the oldest whorehouse in Japan, witness Ninjas in training, and even go on a haiku course. Next up, paddleboarding with Romesh Ranganathan and minigolf with Joe Lycett. Unlike the other activities, the haiku-writing does offer some insight into Bond’s character, however. While he can’t get to grips with the format (seven syllables in the middle, five in the first and last line. If you ain’t poetic no need to sweat it, haikus don’t need to rhyme) it’s a great piece of poetry that gives the book its title: “You only live twice; once when you are born, and once when you look death in the face.” It reveals Bond’s mindset more than the lame opening chapters and builds further foreboding for his journey into Shatterhand’s Hell.

Up until this point there has been remarkably little plot; Bond receives his mission early in the novel and then takes forever to undergo it, plus we’ve yet to meet a villain or a Bond girl. This wouldn’t be a problem if the novel were more character-focused but Bond is explored to just the bare minimum given the circumstances. There’s little deep insight. But things finally pick up when, yes, Bond discovers that the Shatterhands are actually Blofeld and Irma Bunt, because of course they are. Bond keeps it to himself so he can continue his vendetta without interference. I do wonder whether he should have always known it was Blofeld. Revenge should be all Bond thinks of but he doesn’t even mention the concept until this point in the story. Fleming uses Blofeld’s appearance as a twist when it would be more satisfying for Bond to be actively seeking out his nemesis the whole time. Bond is once again described as St George off to kill the dragon, as well as a Japanese legendary figure too, with Fleming now committed to the character as an almost mythological hero after trying, and failing, to dispel that idea in The Spy Who Loved Me.

In preparation for his mission, Bond stays with Kissy Suzuki on Kuro Island, a naked pearl diver who was once a Hollywood actor now returned to her simpler life. She’s a quantum of western solace for Bond, who has struggled to acclimate to the country but now finds the right balance of exotic and familiar in Kissy. She represents a possible out for Bond: could he retire to the simple life on the island too? I loved this section of the book, not because the plot kicked into gear but because it seemed to be finally saying something about Bond, and has a wonderful sense of place and atmosphere. Spending a few days diving with Kissy and her cormorant David Niven (don’t ask) is a period of beauty and serenity that rejuvenates Bond. Confronting death might not symbolise a second life after all, but this place could.

In preparation for his mission, Bond stays with Kissy Suzuki on Kuro Island, a naked pearl diver who was once a Hollywood actor now returned to her simpler life. She’s a quantum of western solace for Bond, who has struggled to acclimate to the country but now finds the right balance of exotic and familiar in Kissy. She represents a possible out for Bond: could he retire to the simple life on the island too? I loved this section of the book, not because the plot kicked into gear but because it seemed to be finally saying something about Bond, and has a wonderful sense of place and atmosphere. Spending a few days diving with Kissy and her cormorant David Niven (don’t ask) is a period of beauty and serenity that rejuvenates Bond. Confronting death might not symbolise a second life after all, but this place could.

Finally, Bond infiltrates Blofeld’s base. It’s not a volcano like the movie but rather a true house of horrors. Described as both “Dracula’s Castle” and the “Disneyland of Death,” the terrifying location serves as Bond’s heart of darkness, a representation of death and fear he needs to overcome after the loss of Tracy. I love Bond’s slow journey trough the dangerous gardens and the horrors he sees on the way. A man with a swollen head is eaten alive by piranhas. A man in a business suit walks into a fumarole and melts, only his top hat remaining like some sort of demented cartoon. “James Bond felt he was living inside a dream,” as Fleming puts it. It’s certainly the most surreal the franchise has ever gotten and I loved how dark and disturbing the book suddenly became, finally fully committing to something. The sequence is unique to the series in terms of tone but unfortunately not plot. This is now the third time Bond has stayed on the island across from the baddie’s lair and swam across to infiltrate.

Ernst Stavro Blofeld is insane. He speaks in a “lunatic, Hitler scream” and describes himself as “a man not only unhonoured and unsung, but a man whom they hunt down and wish to shoot like a mad dog.” As with On Her Majesty’s Secret Service, I’m disappointed with his portrayal here. Thunderball set up a legitimately threatening and intelligent villain like Bond had never faced before but Blofeld is now the antithesis of that cool and confident character. I know that’s the point, that he’s losing his mental faculties with each defeat at the hands of Bond, until he’s nothing but a bitter man grasping for power, but it’s frustrating we never saw Bond properly go up against Blofeld in his original state. I don’t think he’s a particularly great villain here but he works as a driving goal for Bond and a symbol of evil and death. It’s also good to see Irma Bunt again. She does nothing of value but at least she’s there, unlike the films where she murders Tracy and then is never seen or mentioned again.

Ernst Stavro Blofeld is insane. He speaks in a “lunatic, Hitler scream” and describes himself as “a man not only unhonoured and unsung, but a man whom they hunt down and wish to shoot like a mad dog.” As with On Her Majesty’s Secret Service, I’m disappointed with his portrayal here. Thunderball set up a legitimately threatening and intelligent villain like Bond had never faced before but Blofeld is now the antithesis of that cool and confident character. I know that’s the point, that he’s losing his mental faculties with each defeat at the hands of Bond, until he’s nothing but a bitter man grasping for power, but it’s frustrating we never saw Bond properly go up against Blofeld in his original state. I don’t think he’s a particularly great villain here but he works as a driving goal for Bond and a symbol of evil and death. It’s also good to see Irma Bunt again. She does nothing of value but at least she’s there, unlike the films where she murders Tracy and then is never seen or mentioned again.

The castle break-in is a good sequence, though in classic Fleming fashion a little rushed considering the enormous build-up. Bond is captured and forced to sit on a seat that blows hot mud up his arse but he persuades Blofeld to have a civilised chat instead. Although, naturally, this devolves into a brief naked sword fight. It’s a thrilling ending and enjoyably ridiculous. I wasn’t sure what Fleming was going to throw at the wall next, but most of it sticks. Blofeld has the ultimate villain speech that makes every monologue Fleming has written feel like mere prologue, decrying his excellence, before Bond counters it with a very simple “Die, Blofeld! Die!”, something taken for No Time to Die. Bond strangles Blofeld, which would be more satisfying if Bond hadn’t killed Goldfinger the exact same way, uses the mud-melt-arse-seat to explode the castle somehow, and escapes the building on a hot air balloon before crashing down into the water to an unknown fate.

You Only Live Twice suddenly turns epistolary when the penultimate chapter takes the form of Bond’s obituary, published in The Times and written by M. Naturally, reading it brings about a sense of closure to Bond’s story but it goes further than his apparent death. Within we finally learn details of his youth, of his beginnings in the Service, creating, retroactively, this full circle picture of Bond’s life. Not only that but it also supplies the details for Charlie Higson to write his Young Bond series of novels that I read as a kid, and feel tempted to read again now. I like the obituary except for one self-indulgent part. It mentions that a friend of Bond has written books based on his adventures, with a sprinkle of artistic license. Fleming has tied himself into his own narrative and these books I’ve been reading are apparently canon in the world of Bond, or rather the world of Bond is indeed our world and not a fictional one. It’s an unnecessary and distracting step into the world of meta in my eyes, and it feels embarrassing that Fleming wants his fictional creation to be his friend.

You Only Live Twice suddenly turns epistolary when the penultimate chapter takes the form of Bond’s obituary, published in The Times and written by M. Naturally, reading it brings about a sense of closure to Bond’s story but it goes further than his apparent death. Within we finally learn details of his youth, of his beginnings in the Service, creating, retroactively, this full circle picture of Bond’s life. Not only that but it also supplies the details for Charlie Higson to write his Young Bond series of novels that I read as a kid, and feel tempted to read again now. I like the obituary except for one self-indulgent part. It mentions that a friend of Bond has written books based on his adventures, with a sprinkle of artistic license. Fleming has tied himself into his own narrative and these books I’ve been reading are apparently canon in the world of Bond, or rather the world of Bond is indeed our world and not a fictional one. It’s an unnecessary and distracting step into the world of meta in my eyes, and it feels embarrassing that Fleming wants his fictional creation to be his friend.

But rest assured, dear reader, James Bond isn’t dead. He’s back on Kuro Island with amnesia, genuinely believing himself to be a Japanese fisherman. I guess they don’t have mirrors in fishing villages. Kissy is supporting Bond’s delusions, refusing to tell him his past, in order to keep him for herself, which is an incredibly dark turn for a character who up to this point I liked a lot, yet it is played as romantic. She even becomes pregnant with Bond’s child. This could be his titular second life, an almost happy-ish ending with closure. And actually, I think I would like this as an ending for the series knowing that Fleming will die before completing the next novel, leaving only a first draft to be published with no real ending forthcoming. But no, Bond reads a Russian word in a newspaper and thinks the answer to his identity lies with the Soviets, setting out on an adventure to the home of his enemies convinced they are allies. It’s an interesting twist of an ending that I’m curious to see resolved.

Finally reading You Only Live Twice as a fan of the Bond films was an interesting experience, especially in the wake of No Time to Die. That modern movie feels much more like an adaptation than the actual 1967 adaptation, with the poison garden, island stronghold, Bond’s child, and even him mourning the loss of a lover being key factors. You Only Live Twice is very much a novel of two halves. There’s a great Bond adventure in there but it is stretched thin. The second half, once Kissy appears, is emotional, surreal, and thrilling. The first half, not so much. There’s barely a plot, instead just a framework for sightseeing and political discussions. Bond does go on a fascinating character journey, the novel beginning with Bond willing to give up his old life and ending with him actively seeking it out, but there was so much potential for delving deep into Bond after the death of Tracy that feels barely explored. Overall, it’s a fun book but feels like a half measure.

Finally reading You Only Live Twice as a fan of the Bond films was an interesting experience, especially in the wake of No Time to Die. That modern movie feels much more like an adaptation than the actual 1967 adaptation, with the poison garden, island stronghold, Bond’s child, and even him mourning the loss of a lover being key factors. You Only Live Twice is very much a novel of two halves. There’s a great Bond adventure in there but it is stretched thin. The second half, once Kissy appears, is emotional, surreal, and thrilling. The first half, not so much. There’s barely a plot, instead just a framework for sightseeing and political discussions. Bond does go on a fascinating character journey, the novel beginning with Bond willing to give up his old life and ending with him actively seeking it out, but there was so much potential for delving deep into Bond after the death of Tracy that feels barely explored. Overall, it’s a fun book but feels like a half measure.

Stay tuned to OutofLives for my thoughts on the thirteenth of Fleming’s Bond books, and the final novel, The Man with the Golden Gun, in the coming weeks.