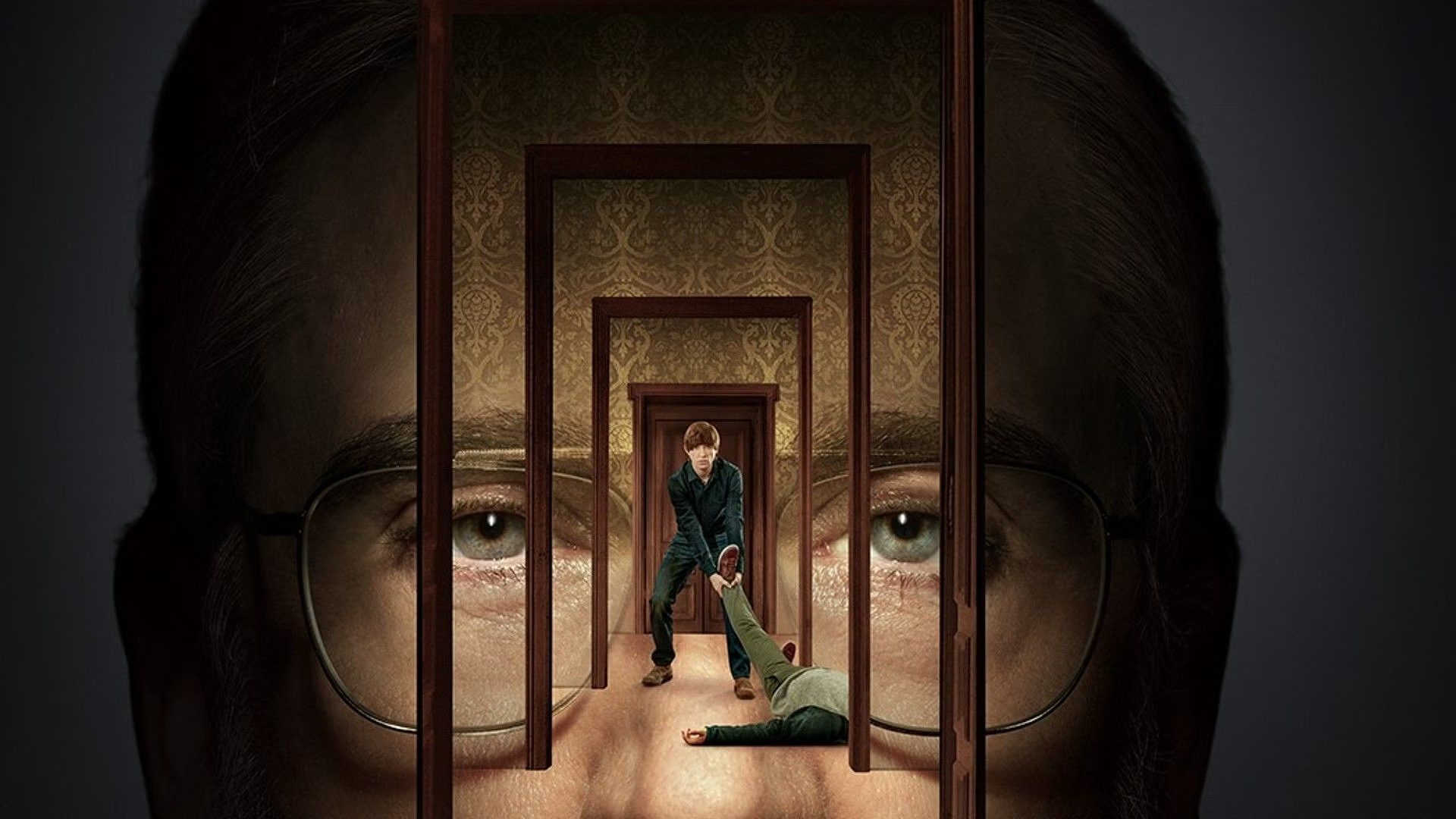

“Let’s try to slow down a little bit. In this space, let everybody finish what they’re saying. When we go more slowly, usually everybody thinks a little more clearly.” This quote from The Patient’s third episode is the perfect summation of my feelings towards the opening episodes of the show. The psychological thriller has great premise, a serial killer kidnaps his therapist and keeps him tied up in his basement as a deluded step towards self-improvement, but watching those first few episodes of the 10-part miniseries, something felt off. It was intriguing, occasionally thrilling, but the beats never hit a strongly as they could have. The show has a problem with patience and pacing.

The Patient is a series so afraid of being boring that it rushes through so much of its initial drama. The writers – Joel Fields and Joe Weisberg, known for The Americans, a show I love – seem equally scared and excited at the prospect of writing a show featuring two characters in a basement. They try all the cheap tricks to make it engaging – short scenes, 20-minute episodes, punchy cliffhangers – when the story demands to take it slow and spend time with these characters in this strange circumstance. Just look at Inside No. 9, one of, if not the best show on television, if you want to see how engaging and dynamic two-man, single-location plays on television can be.

Rather ironically, The Patient demands patience from the viewer yet has none itself. In the US, the show aired an episode a week, and while I’m usually all for weekly viewing to allow time to properly digest each instalment, twenty minutes a week is not a full meal. Blessedly, the entire series debuted at once in the UK and I doubt I’d have kept with it if it hadn’t. The short runtimes actively damage the drama of the episode. Therapy scenes between therapist Alan (Steve Carell) and patient Sam (Domhnall Gleeson) often cut away halfway through to the next scene despite the conversation clearly going on for longer. This is a pet peeve of mine about modern TV writing – ending on a character asking another a question and we not hearing how they answer. In this show, not seeing the end of therapy scenes is disastrous. Every interaction between these two men is vital. The way the show is put together highlights that it is a structured narrative rather than a naturally-evolving story.

Alan spends days and days, ultimately weeks and weeks, chained to a bed and confined to a single room. Yet the show never puts the effort into presenting this. The audience never gets a good sense of his time there. It should be like June in The Handmaid’s Tale, getting to know every inch of the room she’s kept in, seeing how he actually lives in those conditions: how he washes, relieves himself, and trims his immaculate beard and hair. He would feel agonising boredom but the show doesn’t commit to it because it’s too scared of being boring itself. What could be the tensest and most dramatic scenes are also lessened by the show’s need to rush. In one scene Alan leaves a jug, or pitcher, he’s been imagining killing Sam with on the table they share but the show draws no attention to it. I want the drama to be milked for all it’s worth. I want to see Alan place it there, think about it, prepare his actions, glance at it during the conversation, and then decide against it. But as it stands, it is simply there in one scene and not in the next.

Fields and Weisberg are capable writers and the conversations between Alan and Sam can be riveting, when they allow them to be. The actors are great throughout but I want long, engrossing therapy sessions like In Treatment or the interviews in Mindhunter. Scenes that make me lean in, full of expert folly work of creaking chairs and shuffling clothes. In the early episodes, the scenes are far too fast. There’ll be a great one-minute chat before it suddenly cuts before the conversation is over to Alan mediating afterwards and remembering a flashback to try and keep the audience engaged even though we already were! I know presenting the passage of time is necessary but putting all these short therapy sessions into one long scene which lets everything breathe would be much better.

The only thing the show does take its time with from the very beginning is listening to Sam urinating just before he visits Alan each day, which is a detail I love. It shows that Sam is comfortable, perhaps too much so, with Alan’s presence, that he lacks regular social graces and embarrassment, and treats his therapist as a tool in his basement just like the toilet. He doesn’t see a difference between physical and mental release. Of course, it also serves a practical reason in a later episode when Alan rushes to do something in the time it takes Sam to urinate, having learnt his procedure. I wish there were more weird but insightful details like this throughout the show.

Thankfully, the series builds on the potential it shows in the early episodes and gradually calms, allowing for episodes with longer runtimes and full scenes and conversations between the characters. The Patient never truly excels but it is a solid watch by its midpoint but then, again, the finale hints at some story aspects, like Sam wanting a replacement father more than a therapist, that are a little rushed, but the show does grow more confident and assured, ultimately ending on a surprising point that I felt worked, but I’m sure some will feel otherwise.

What are your thoughts on The Patient? Let me know in the comments and be sure to geek out with me about TV, movies, and video-games on Twitter @kylebrrtt.