For a show that is 80% people climbing stairs and checking into hotel rooms, Ripley is the most engrossing new television series in some time. It’s a throwback: in clear superficial ways, like the black-and-white cinematography and period setting, but at its heart, too. The 8-part adaptation of Patricia Highsmith’s classic thriller novel The Talented Mr. Ripley embraces old school suspense filmmaking. It’s a mixture of modern television and Hitchcock, film noir, and even Italian cinema.

Ripley is a loving throwback in a visual sense. The Italy on display is shot sumptuously. The Caravaggio-esque light and shadow both beautiful and connected to the plot and themes. I’ve missed TV where every shot and moment is brilliantly composed. Writer/director Steven Zaillian directs the hell out of it. Everything feels deliberate, including the pace, which may be too slow for some.

What I love most about the series is how it handles death, specifically the aftermath. In most shows, death is the release of tension. It’s what the whole drama is building to, a sudden outburst of violence after being teased for so long. It can be effective or feel cheap. In Ripley, death is just the start of the tension; the appetizer before the main course, far from a moment of catharsis. Each murder might seem inevitable but they turn their respective episode on its head. It reminded me most of The Sopranos, especially Ralphie’s death in season 4, happening shockingly halfway through an episode that then pivots completely to be about the disposal of his body.

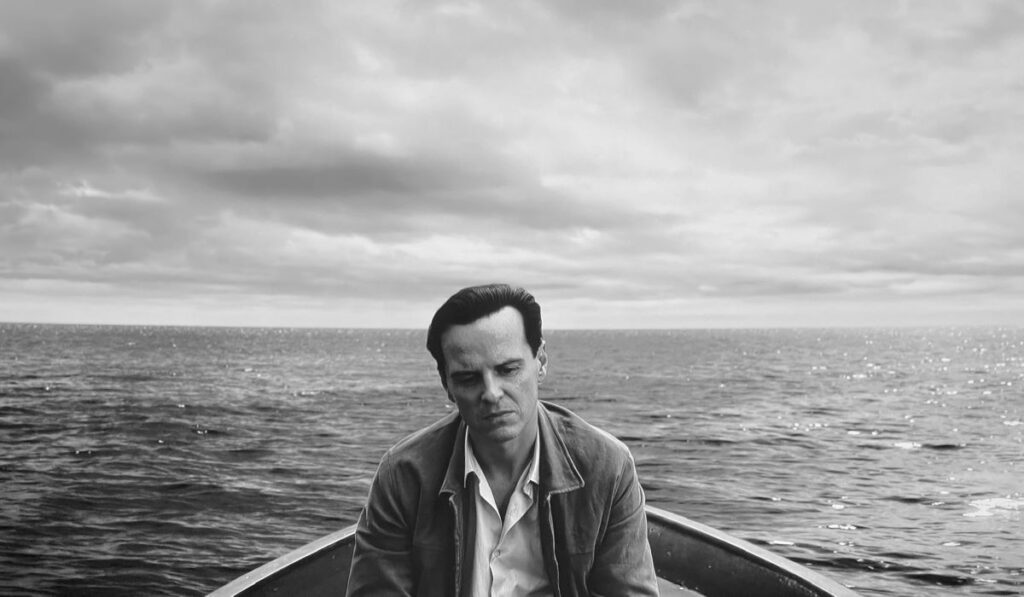

The killings themselves are fairly perfunctory. Tom Ripley, to enact or maintain his identity theft plan, kills two men. Blows to the head with heavy instruments, an oar on a boat and an ashtray in an apartment. It’s what follows, the cleanup of each death, that are the true masterful set pieces of the series.

With 30 minutes remaining of the third episode, Tom kills his apparent friend Dickie and that final half hour is an all time great sequence of television as he tries to hide what’s happened. The cleanup does two diametrically opposed things at once. It shows how much of a psychopath Tom is yet also makes us care for him. His actions are haphazard, he’s clearly not entirely sure what he’s doing. And it just keeps going wrong.

Every step is an excruciating challenge. Every step a trial. It begins small, like Tom not being able to take off Dickie’s ring and he eventually uses blood as a lubricant. After his initial hubris of smoking a cigarette, another boat appears and Tom has to drive away, then the rope of his makeshift anchor trips him up and he falls off the boat, then the boat hits him, then the anchor hits him, then the long, arduous climb back onto the boat, then he tries to burn the boat but it doesn’t burn, then he has to sink the boat but the bay is barely deep enough.

The sequence builds sympathy for Tom, we want him to succeed and it makes us forget what he’s done. Suddenly the killer is the underdog. Everything that can go wrong does go wrong; it’s tense and darkly hilarious. I love stories like that, ones that just keep escalating, like the episodes of The Leftovers that focus on Christopher Eccleston’s character. Here Tom has to face his childhood fear, water, and we cheer when he overcomes it. The length of the sequence is vital to build a connection to Tom, to begin to root for him, because it’s the emotional connection that holds the rest of the season together. We still want him to get away despite what he’s done.

The boat sequence also just looks fantastic. I don’t know how they shot it but it’s very impressive. Usually two actors on a boat in the middle of the sea looks awful, a green screen nightmare, like in the otherwise brilliant Midnight Mass, but here it’s great. The lack of music is a striking detail, the entire scene soundtracked to the sound of waves lapping at the boat. Tom painstakingly washing each of Dickie’s items in the water is also a good detail, calling back to classic imagery of trying to cleanse blood and sin. We probably should have seen some of Tom’s blood though considering the injuries he sustains. Hit by a boat and an anchor with nary a bruise.

The second cleanup is less clumsy, more considered, and far more unsettling. Tom kills the curious Freddie and the final 37 minutes of the fifth episode become an almost silent movie of unbearable tension, bringing to mind Rififi. The sequence shows the true darkness of Tom and plays with the idea of making the viewer a voyeur. There is a focus on the cat Lucio, watching Tom move and dispose of the body, just like we are, the watcher of this silent macabre play.

Tom’s methodology is only matched by director Zaillian. We see every detail. Every trip to the sink to wring out blood. Every opening and closing of the lift doors. Every step Tom has to drag the corpse down. The show takes great pleasure in the minutiae of small repetitive details throughout, just as Tom does so he can copy them, from the tapping of a cigarette box to the clicking of pens, and the same is true for these cleanup scenes. The details and sound design are so rich, including the creak of the lift, the echoed footsteps, and Freddie’s head repeatedly hitting the ground. Even how hard and awkward it is to manhandle a body is taken into consideration.

The episode is gorgeously shot but the direction is also purposeful to the story. Making the viewer understand the geography of a location like Tom’s apartment building that he has to navigate late at night with a corpse in tow is as vital as presenting its beauty. It’s a terrifically tense sequence, though not without some dark humour. A laugh comes from Tom finding Freddie’s car, hoping to use it to dispose of the body, only to see it’s the smallest on the street, a Fiat 500. And after almost 40 minutes of painstaking, anxiety-inducing cleanup, the final shot showing some blood remaining on the stairs is sure to make every viewer utter “oh no!” despite the fact we should want Ripley to be caught.

How does this show look this good? I found myself asking this of Ripley, because it looks far better than the regular Netflix output. The answer: because it’s not a Netflix production. It was shot for Showtime but, because of bankruptcies and acquisitions, it was sold to Netflix. That also makes future seasons, based on the sequel novels, unlikely. But I’m fine with that, I like it as a limited series. A giallo spin-off featuring Inspector Ravini would be much appreciated, however.

As great as Ripley is, the masterful post-murder scenes maybe had an unexpected negative consequence on the finale: I never believed Tom was going to kill Marge because there wasn’t enough time left in the series to show the extensive, extended cleanup.