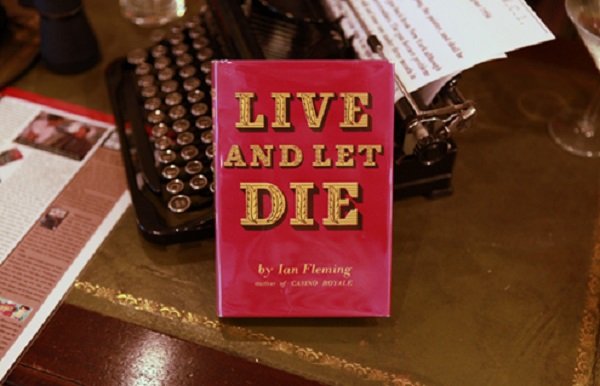

There’s now a hint of anger in James Bond’s cold grey-blue eyes. After the events of Casino Royale, Bond is restless and awaiting a chance to get revenge on the villainous SMERSH, something he’s soon offered when M sends him to New York to investigate criminal kingpin and possible Russian agent Mr. Big. Immediately, Live and Let Die proves itself to be a very different book than Casino Royale. Fleming’s first James Bond adventure was a classy thriller concerned with the secret agent questioning his own philosophy, while the second turns up the pulp factor and embraces the ‘get the girl, kill the baddie’ formula that provides simple but effective thrills. But, reading it for the first time in 2021, it’s the 1954 novel’s depiction and exploration of race that dominates my thoughts. As the introduction to the book, written by Louise Welsh, asks, do you read it with post-modern irony or as a barometer for social change?

It’s not just the perception of racial issues which separates the 50’s reader from that of the present day but the exact nature of the thrills the novel offers too. The opening line of Live and Let Die is “There are moments of great luxury in the life of a secret agent.” It’s worth noting that the book was first published the year that rationing ended in Britain and the many, many descriptions of food and drink were once just as thrilling as the spycraft and action. Welcomed into the USA by men named Halloran and Grady (Stephen King must have read this while writing The Shining), Bond is taken to an incredible hotel suite in New York City. This is a tale that will take Bond from the immense luxury of his life, from the heights of a New York skyscraper, all the way down to the depths of the criminal underworld and to the dangers of the seabed, literally stripping him of his possessions and placing him closer to death than ever before.

It’s not just the perception of racial issues which separates the 50’s reader from that of the present day but the exact nature of the thrills the novel offers too. The opening line of Live and Let Die is “There are moments of great luxury in the life of a secret agent.” It’s worth noting that the book was first published the year that rationing ended in Britain and the many, many descriptions of food and drink were once just as thrilling as the spycraft and action. Welcomed into the USA by men named Halloran and Grady (Stephen King must have read this while writing The Shining), Bond is taken to an incredible hotel suite in New York City. This is a tale that will take Bond from the immense luxury of his life, from the heights of a New York skyscraper, all the way down to the depths of the criminal underworld and to the dangers of the seabed, literally stripping him of his possessions and placing him closer to death than ever before.

The novel’s plot is often a tug of war between the realism of Casino Royale and utter preposterousness. On one hand, SMERSH’s plot to support a Black American gangster to weaken its enemies and make money is genius, and on the other its bonkers because the narrative revolves around the discovery and trade of Henry Morgan’s lost gold in the Caribbean. The criminal enterprise is treated seriously, especially when the action is in Harlem, yet it’s all to do with pirate treasure, like if the Sopranos suddenly started talking about doubloons between mouthfuls of gabagool. It does very much feel like Fleming had an interest in pirate history while living in Jamaica and decided not to let his research go to waste, cramming the information into a novel where it doesn’t naturally fit.

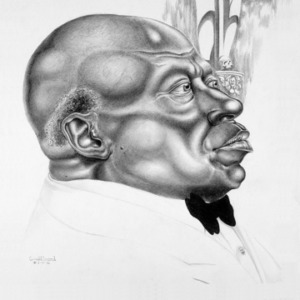

“The negro races are just beginning to throw up geniuses in all the professions – scientists, doctors, writers. It’s about time they turned out a great criminal. They’ve got plenty of brains and ability and guts. And now Moscow’s taught one of them the technique.” M states this of Mr. Big during his briefing to Bond. Mr. Big and his operation clearly play on the fears of the 1950s and the perceived threat of a Black uprising at that time. The police won’t make a move against him in fear of a race riot. His appearance and stature are at once almost progressive considering he will prove himself a most dangerous and intelligent adversary against Bond, but also sadly steeped in stereotypical and now outdated details based on his heritage. Mr. Big uses voodooism to strike fear in the Black population, who are always written as firm believers of the practice and are terrified at the prospect ‘The Big Man’ is a zombie of Baron Samedi. “The fear of voodoo and the supernatural, still deeply, primevally ingrained in the negro subconscious.”

“The negro races are just beginning to throw up geniuses in all the professions – scientists, doctors, writers. It’s about time they turned out a great criminal. They’ve got plenty of brains and ability and guts. And now Moscow’s taught one of them the technique.” M states this of Mr. Big during his briefing to Bond. Mr. Big and his operation clearly play on the fears of the 1950s and the perceived threat of a Black uprising at that time. The police won’t make a move against him in fear of a race riot. His appearance and stature are at once almost progressive considering he will prove himself a most dangerous and intelligent adversary against Bond, but also sadly steeped in stereotypical and now outdated details based on his heritage. Mr. Big uses voodooism to strike fear in the Black population, who are always written as firm believers of the practice and are terrified at the prospect ‘The Big Man’ is a zombie of Baron Samedi. “The fear of voodoo and the supernatural, still deeply, primevally ingrained in the negro subconscious.”

When Fleming isn’t obsessing over his race, Mr. Big is actually a great Bond villain and is much more of a proto version of the monologuing bad guys I know from the films than Le Chiffre was in Casino Royale. He’s a perfectionist who has no more worlds to conquer in his chosen orbit. So preeminent in his profession, that of money and death, he now only cares about the artistry and technical polish of such matters. He strives to smuggle and kill in flawless yet thrilling ways and Bond not only finds himself on the receiving end of Mr. Big’s speeches but the discussed death traps too. Of course, he has a health condition or disability like his fellow antagonists in the series, namely a heart condition that gives him grey skin. Having recently watched The Americans and being impressed how that show examined Gregory, a Black American working for the Russians, it was annoying that Fleming refused to look at why Mr. Big would aid the Soviets and how they likely treated a Black man like him with more respect than Americans. Mr. Big’s argument for why the discovered gold belongs to him is also intriguing: slaves hid the gold; they should earn it.

The opening few chapters of Live and Let Die feel relatively aimless. Bond already knows everything by the time he reaches America, having been briefed on Mr. Big’s operation beforehand. There’s no mystery to uncover as Bond explores New York. However, I think this is because the book is concerned with making a point about experience. Bond will read information in a book or document, whether it be on voodoo, killer fish or the streets of Harlem, and this gives him and the reader all the necessary plot details, all the exposition. And then Bond will venture out to experience these things first hand because he needs to see how they compare to what he’s heard. This is good for understanding Bond’s character but not for the overall storytelling – nothing of the plot comes from his actions, just character work. Preferably these two elements would be in tandem but this way plot and character are separated, almost as cleanly as alternating chapters.

The opening few chapters of Live and Let Die feel relatively aimless. Bond already knows everything by the time he reaches America, having been briefed on Mr. Big’s operation beforehand. There’s no mystery to uncover as Bond explores New York. However, I think this is because the book is concerned with making a point about experience. Bond will read information in a book or document, whether it be on voodoo, killer fish or the streets of Harlem, and this gives him and the reader all the necessary plot details, all the exposition. And then Bond will venture out to experience these things first hand because he needs to see how they compare to what he’s heard. This is good for understanding Bond’s character but not for the overall storytelling – nothing of the plot comes from his actions, just character work. Preferably these two elements would be in tandem but this way plot and character are separated, almost as cleanly as alternating chapters.

Bond reunites with CIA agent Felix Leiter and the two explore Harlem together. For a sizable portion of the novel, Felix is not only Bond’s friend but his sidekick, and I enjoy their relationship. If you pardon the pun, the American brings out the lighter side of Bond. He’s certainly more quippy and less grumpy than he was in Casino Royale. Leiter acts as Bond’s tour guide to Harlem and reveals he’s fond of African Americans. He wrote a few pieces on Dixieland Jazz and a review of Orson Welles’ all-black Macbeth for a publication, and explains this to Bond with the enthusiasm of someone who loves a bit of cultural appropriation. Other than a few rare instances, Bond doesn’t make his opinion on African Americans known, except that he finds the girls beautiful, of course. Many characters comment on race, both positively and negatively, but Fleming is careful not to reveal many of Bond’s thoughts on the subject. Depending on the reader’s own opinions, Bond could be a progressive liberal or a massive racist.

Live and Let Die occasionally shifts its perspective away from Bond to “The Whisper”, Mr. Big’s chief phone operator who organises the vast criminal network and speaks very softly like a 1950’s ASMR-ist. This does a great job of building tension as we learn of the vast numbers watching Bond and relaying his position until it’s time to strike. This huge network is such a great idea, especially with most African Americans at the time working service jobs that are ignored by the White population and so the enemy could be anywhere. Disappointingly however, Fleming plays it like the enemy is everywhere with every Black character in Harlem treated as a criminal. The novel is at its most cringey when Bond and Leiter go to a Harlem bar just to listen into the patrons’ conversations like they are visiting a zoo. Fleming tries his hand at writing in dialect for these conversations and they have to be read to be believed, the author thinking he’s the “I speak jive” woman from Airplane.

The lackadaisical feel of the novel suddenly disappears once Bond and Felix are captured by Mr. Big; while Live and Let Die may meander, it always delivers when Bond is placed in immediate danger and Fleming is great at portraying sudden bursts of intense action and peril. It’s here where Bond first comes face-to-face with the villain and his finger is broken in sickening detail. Bond wasn’t a man of action in Casino Royale, and while he’s captured, tortured and only barely escapes here, it’s more than he ever did in the previous novel. He kicks henchman Tee-Hee down some stairs and shoots two men to escape – his first confirmed kills of the series – before stealing a car and driving away.

While being interrogated by Mr. Big, Bond is watched by Solitaire who determines whether the secret agent is lying. She’s something of a psychic, having been given a drink of dirt, gunpowder, rum, and human blood as a girl, although her powers never work when needed, making her the Deanna Troi of the James Bond canon. The beautiful young woman is from a family of slave owners and so Mr. Big keeps her as his slave and even plans to marry her against her wishes. She contacts Bond after he escapes and begs him to take her with him, saying that she’ll kill herself if he doesn’t help. It’s not stated whether this acts as a cruel reminder of Vesper, or whether Fleming writes all his woman as suicidal if Bond doesn’t save them, but he agrees and the two flee by train on a romantic getaway to Florida. Not only is losing Solitaire a blow for Mr. Big but Bond is also promised sex as part of the deal, although not until his broken finger heals (he needs it apparently). Solitaire is barely a character and is even described at one point as “Solitaire, the ultimate personal prize”.

While being interrogated by Mr. Big, Bond is watched by Solitaire who determines whether the secret agent is lying. She’s something of a psychic, having been given a drink of dirt, gunpowder, rum, and human blood as a girl, although her powers never work when needed, making her the Deanna Troi of the James Bond canon. The beautiful young woman is from a family of slave owners and so Mr. Big keeps her as his slave and even plans to marry her against her wishes. She contacts Bond after he escapes and begs him to take her with him, saying that she’ll kill herself if he doesn’t help. It’s not stated whether this acts as a cruel reminder of Vesper, or whether Fleming writes all his woman as suicidal if Bond doesn’t save them, but he agrees and the two flee by train on a romantic getaway to Florida. Not only is losing Solitaire a blow for Mr. Big but Bond is also promised sex as part of the deal, although not until his broken finger heals (he needs it apparently). Solitaire is barely a character and is even described at one point as “Solitaire, the ultimate personal prize”.

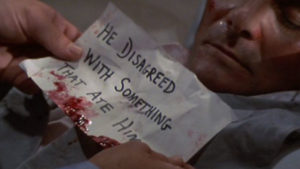

Bond, and therefore Fleming – the author using the spy as a mouthpiece for his own opinions – does not like Florida. It’s like Torquay but a million times worse. Bond is repulsed by the “oldsters” who make up a large part of the state’s population and he meets with Felix again just to drive around town and gawk at them. It’s clear Fleming has something of a love/hate relationship with America, something I’ve heard will develop in further novels. He calls it “Eldollarado” and is torn between the sense of freedom the country exudes but also the facile, commercial nature of it. Of course, while Bond is contemplating such matters, Solitaire is captured once again and Felix, questing for vengeance, is fed to a shark while trying to infiltrate Mr. Big’s shipping compound. “He disagreed with something that ate him” says a card mockingly left with his mangled but still alive body. It was fascinating to see this scene that I know from the film License to Kill appear here and learn that the films adapt the novels in much more of a hodgepodge way than I first thought.

Up to this point in Live and Let Die, Bond has missed out on most of the action and big events. A much-teased attack on a train only comes after Bond has departed, and Felix is attacked offscreen (offpage?) while Bond takes a nap. Even his escape from Mr. Big in Harlem is one of desperate, improvised panic. But finally, 180 pages in, Bond becomes a much more active protagonist and breaks into the wharf where Felix was attacked in search of revenge. It’s a great sequence, probably the best of the book, as Bond stealthily enters and sneaks around before finding the gold coins hidden in exotic fish tanks. This is the type of sleuthing and spying I want from a Bond novel and it only gets better when “The Robber” appears, another memorable henchman, who shoots at Bond. Glass, water, and fish go flying in the following engaging action scene and it ends with Bond feeding the villain to his own shark with cold-blooded brutality.

Up to this point in Live and Let Die, Bond has missed out on most of the action and big events. A much-teased attack on a train only comes after Bond has departed, and Felix is attacked offscreen (offpage?) while Bond takes a nap. Even his escape from Mr. Big in Harlem is one of desperate, improvised panic. But finally, 180 pages in, Bond becomes a much more active protagonist and breaks into the wharf where Felix was attacked in search of revenge. It’s a great sequence, probably the best of the book, as Bond stealthily enters and sneaks around before finding the gold coins hidden in exotic fish tanks. This is the type of sleuthing and spying I want from a Bond novel and it only gets better when “The Robber” appears, another memorable henchman, who shoots at Bond. Glass, water, and fish go flying in the following engaging action scene and it ends with Bond feeding the villain to his own shark with cold-blooded brutality.

Sometimes I feel like Fleming is an impatient writer, or maybe just conscious of his word count. After a chapter relishing every thrilling moment of a set piece, the next is often a breakneck detailing of necessary but unexciting events that lead to the next big moment. A chapter of getting things that need to happen out of the way. Bond travelling to a new location, meeting a new contact, and hearing a new monologue of exposition. This happens after Bond’s confrontation with The Robber, where we follow the agent travelling down to Jamaica via a variety of planes, hotel rooms, and restaurants. There is a long, weird passage about fearing dying in a plane crash and how Bond sees such travel as vanity. “You start to die the moment you are born,” Fleming writes in his most emo edgelord moment. But if Bond has survived this far, why not a little longer? As the title suggests, death is a key theme of the novel and many of the people who come into contact with Bond die or nearly die.

Bond is greeted in Jamaica by Strangways, a fairly uninteresting agent keeping watch over the island, and he in turn introduces Bond to Quarrel. Finally, I thought while reading Quarrel’s introduction, a Black character who plays a positive role in the novel and is an aide to James. I liked him immediately and Bond does too. It’s going literally swimmingly until Bond reveals he likes Quarrel because he can hardly tell that he’s Black. “It was only the spatulate nose and the pale palm of his hands that were negroid.” Thankfully, Quarrel is a fun and engaging supporting character, a worthy replacement for the injured Felix, and he spends a little more than a week training Bond for his upcoming excursion to Mr. Big’s fortified island. It’s a great Rocky-esque training montage full of running, swimming and extreme fishing, with Bond desperate to toughen up after gorging on the excesses of the city. Despite some obvious issues, the novel does excel at presenting how Bond operates on a mission, from both the big moments to the day-to-day routine.

Bond is greeted in Jamaica by Strangways, a fairly uninteresting agent keeping watch over the island, and he in turn introduces Bond to Quarrel. Finally, I thought while reading Quarrel’s introduction, a Black character who plays a positive role in the novel and is an aide to James. I liked him immediately and Bond does too. It’s going literally swimmingly until Bond reveals he likes Quarrel because he can hardly tell that he’s Black. “It was only the spatulate nose and the pale palm of his hands that were negroid.” Thankfully, Quarrel is a fun and engaging supporting character, a worthy replacement for the injured Felix, and he spends a little more than a week training Bond for his upcoming excursion to Mr. Big’s fortified island. It’s a great Rocky-esque training montage full of running, swimming and extreme fishing, with Bond desperate to toughen up after gorging on the excesses of the city. Despite some obvious issues, the novel does excel at presenting how Bond operates on a mission, from both the big moments to the day-to-day routine.

Live and Let Die embraces what will become the standard Bond formula, at least with what I’m familiar with as a big fan of the films. The megalomaniacal villain and their speeches, the exotic travel, Bond as an action hero, and the girl to save and sleep with. Casino Royale was a higher standard of narrative – a classy and surprisingly deep adventure – and now, to continue storytelling with this character, Live and Let Die fully embraces the pulp thriller aspects in its finale, contrasting the muted, philosophical denouement of Casino Royale. Strip away the espionage, politics, and fifties specificities, and the ending sees our hero saving a damsel in distress from an island of brutal natives, magic, and hungry sea creatures. It’s an old movie serial, befitting adaptation by Flash Gordon just as much as James Bond.

The novel’s finale is a lightning fast, exciting read. First Bond perilously swims to his enemy’s island and has to face the threat of an octopus and hungry barracuda. My only complaint is that Fleming fills the chapter with so many descriptions of fish. The spotlight is shone on every fish in the sea and it’s clear the author wants to show off his knowledge, just like with the pirate booty. After planting a bomb on Mr. Big’s yacht, Bond is captured and stripped yet again, this time tied to Solitaire, and it seems Fleming is obsessed with bondage. James Bondage. The two are tied to the boat in a deadly practice known as “keel-hauling” in which they will be shredded by the coral reefs and then eaten by sharks as Mr. Big watches on with glee, a scene used in the film version of For Your Eyes Only. Of course, Bond’s bomb detonates, saving the heroic pair while Mr. Big is thrown into the sea and torn apart by the marine life in a shockingly gory death which sees his severed head bob to the surface before being swallowed whole.

The novel’s finale is a lightning fast, exciting read. First Bond perilously swims to his enemy’s island and has to face the threat of an octopus and hungry barracuda. My only complaint is that Fleming fills the chapter with so many descriptions of fish. The spotlight is shone on every fish in the sea and it’s clear the author wants to show off his knowledge, just like with the pirate booty. After planting a bomb on Mr. Big’s yacht, Bond is captured and stripped yet again, this time tied to Solitaire, and it seems Fleming is obsessed with bondage. James Bondage. The two are tied to the boat in a deadly practice known as “keel-hauling” in which they will be shredded by the coral reefs and then eaten by sharks as Mr. Big watches on with glee, a scene used in the film version of For Your Eyes Only. Of course, Bond’s bomb detonates, saving the heroic pair while Mr. Big is thrown into the sea and torn apart by the marine life in a shockingly gory death which sees his severed head bob to the surface before being swallowed whole.

Despite a dull opening and an eventual plot which turns this James Bond tale into a lesser and far more ludicrous adventure than its forebearer, Live and Let Die is ultimately an entertaining read and one seemingly vital in creating the world and feel of literature’s greatest secret agent. It’s a flawed novel, much more so than Casino Royale, and its depictions of race and the language surrounding it make it less accessible and feel its almighty age of almost 70 years. Yet there is still fun and thrills bound between the covers, even if one reads it as a time capsule just as much as a spy adventure.

Stay tuned to OutofLives for my thoughts on the third of Fleming’s Bond novels, Moonraker, in the coming weeks.